poetry month

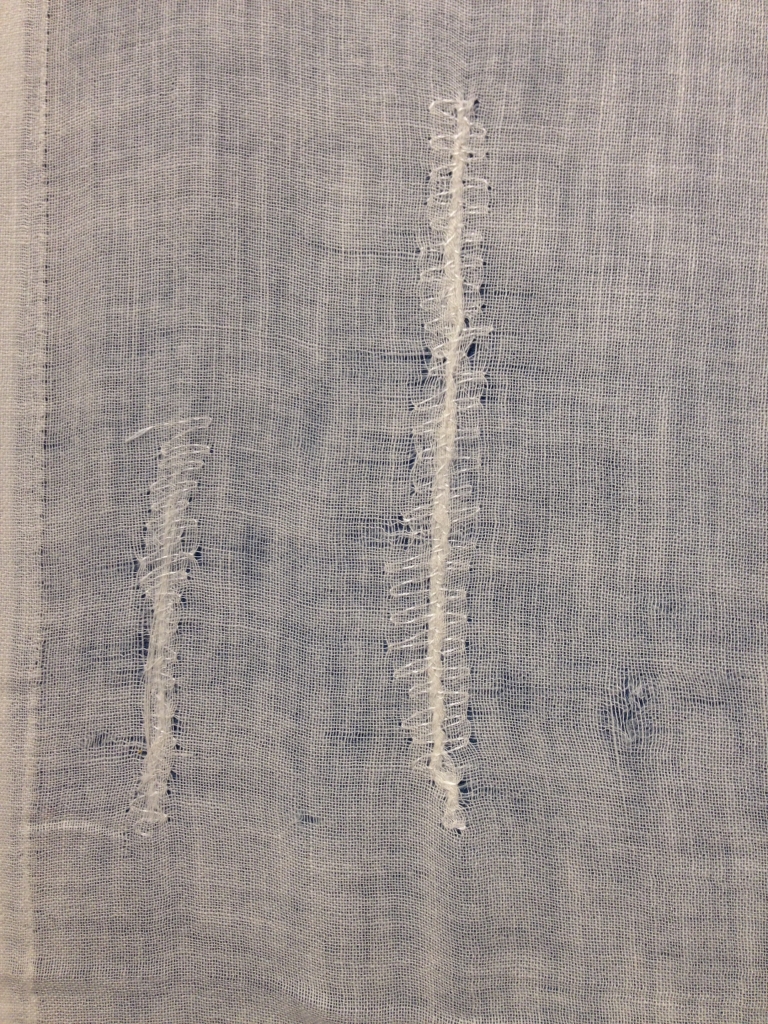

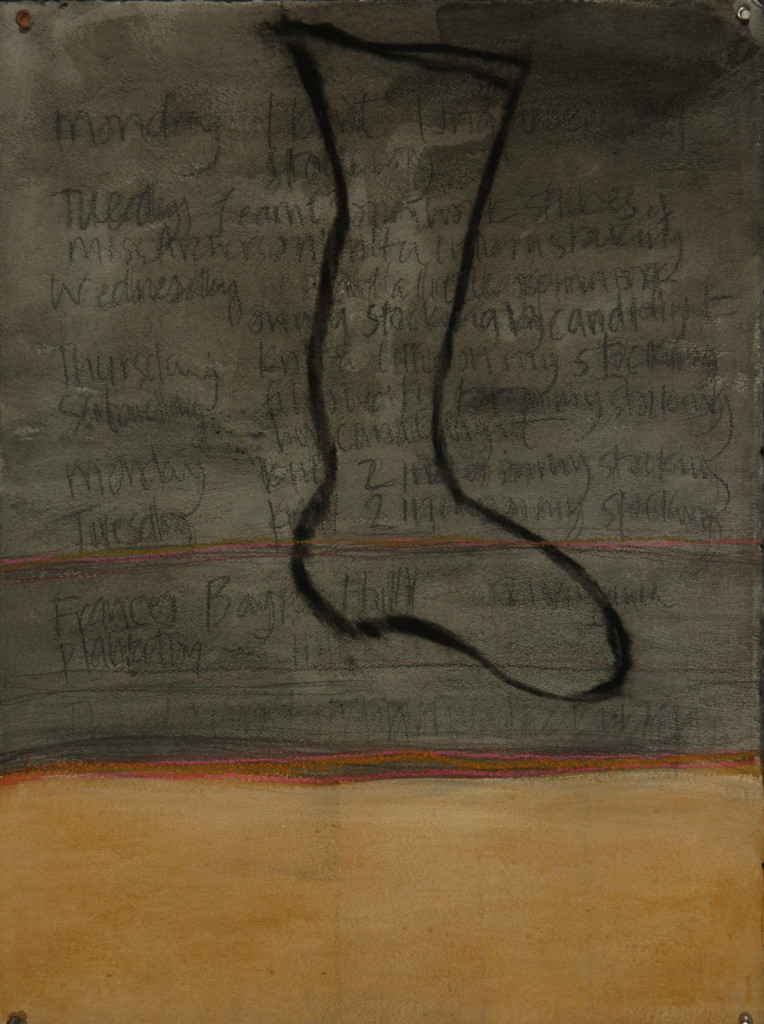

Textile terms are often linked to writing, and in particular, works of women’s words.

Theodore Roethke sets the stage for his glowing review of the poet Louise Bogan (1897-1970) by starting with a contrast, stating that women poets are often accused of ‘lack of range” exhibited by “the spinning out; the embroidering of trivial themes.” He concludes his review by noting: “Her poems create their own reality, and demand not just attention, but the emotional and spiritual response to the whole man. Such a poet will never be popular, but can and should be a true model for the young. And the best work will stay in the language as long as the language survives.”

Perhaps Anne Bradstreet (1612-1672), the first poet of the Colonies, set the standard and bar for women poets in her poem, The Prologue:

I am obnoxious to each carping tongue

Who says my hand a needle better fits.

A poet’s pen all scorn I should thus wrong;

For such despite they cast on female wits,

If what I do prove well, it won’t advance—–

They’ll say it stolen, or else by chance.

Indeed, needle and thread did function as a stylus for many a young girl on the canvas of her sampler as evidenced in the recent exhibition, Hail Specimen of Female Art! New Jersey Schoolgirl Needlwork 1726-1860 held at the Morven Museum and Garden. Over 150 samplers lined the galleries, almost overwhelming to the eye, but reassuring and fortifying for both the scholar and stitcher alike.

Young Anne Rickey (1783-1846) stitched/wrote on her sampler:

Hail specimen of female art

The needle’s magic power to show

To canvas various hues impart

And make a mimic world to grow

A sampler then with care peruse

An emblem sage you there may find

The canvas takes what forms you choose

So education forms the mind.

The poet Dara Mandle links weaving, writing , technology and preservation in her poem, Looking at Burden Baskets in the Smithsonian:

Was the weaver’s art so different

from my picking apart?

She peeled cedar shoots for her daily tools,

I recorded the music of bracken fern

and sumac. On the page, I threaded

wild rye with river cane, she used

a loom to coil deer grass around yucca

Why did I stare? I didn’t imagine her

in a museum inspecting my laptop,

its plastic mouse holy as a scarab.

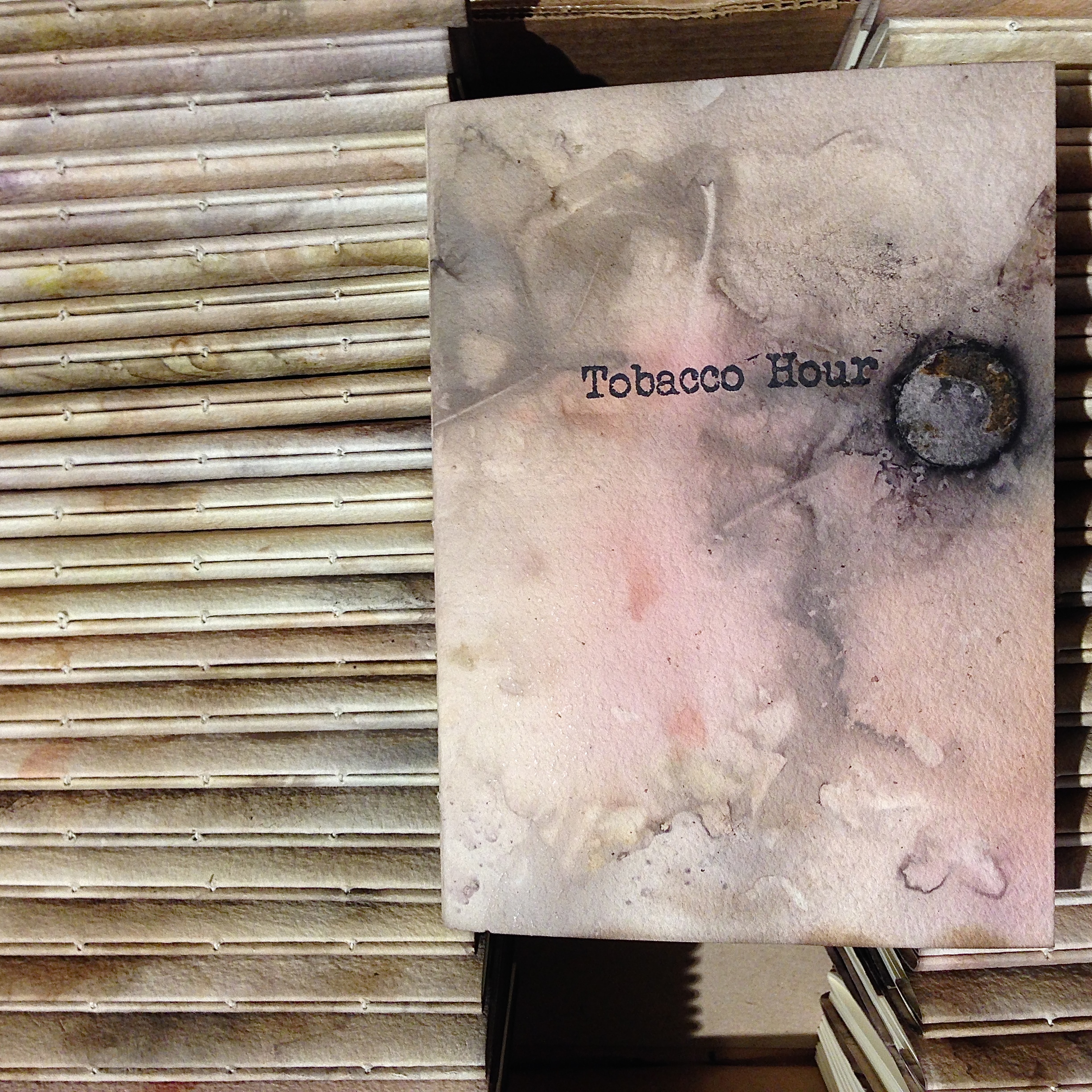

April is poetry month, and seems only fitting for one to venture forth and hear words read from pages of books by their writers. Dara Mandle will be reading from her newly published chapbook, Tobacco Hour (art by Brece Honeycutt), along with writer John Talbird (art by Lesley Kerby) on Sunday April 19 at Luhring Augustine Bushwick from 4-6pm. This event marks the 10th & 11th writer/artist/poet collaborations initiated and produced by Norte Maar.

Psyche The Feminine Poetic Consciousness An Anthology of Modern American Women Poets, edited by Barbara Segnitz and Carol Rainey (Dell Publishing, 1973), pgs. 11, 12 (Both Roethke and Bradstreet from the introduction).

Theodore Roetheke, “A Memorable American Poet, The Poetry of Louise Bogan,” reprinted from the Michigan Alumnus Quarterly Review, December 3, 1960, Vol. LXVII, No. 10, accessed online April 15, 2015, http://www.lsa.umich.edu/UMICH/hopwood/Home/Lecturers%20&%20Readers/Hopwood%20Lectures%20PDF/HopwoodLecture-1960%20Theodore%20Roethke.pdf

Linda Arntzenius, “Hail Morven’s Latest (Landmark) Exhibition”, Princeton Magazine, February 2015, accessed on line April 14, 2015, http://www.princetonmagazine.com/hail-morvens-latest-landmark-exhibition/

Elaine Showalter, A Jury of her Peers: American Women Writers from Anne Bradstreet to Annie Proulx, (Virago Press, 2009), pgs. 99-100.

Dara Mandle, Tobacco Hour, (Norte Maar, 2015).