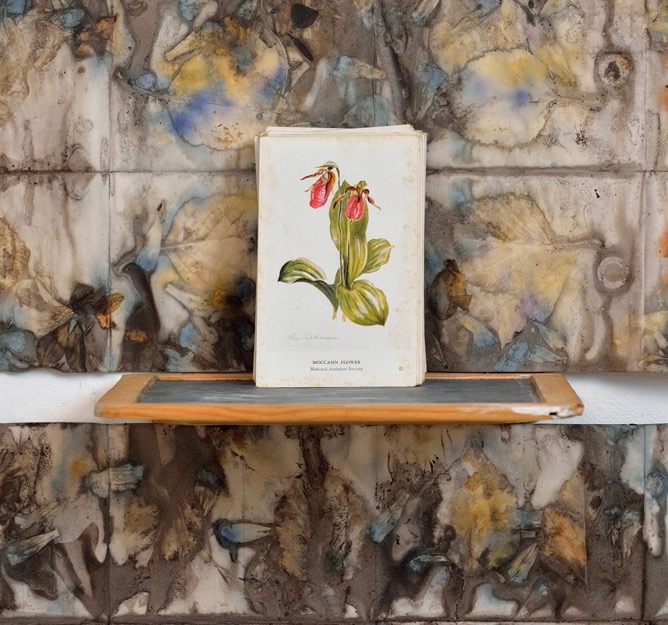

Recently, Sharon Butler of award wining blog, Two Coats of Paint, asked me to compile a list of ten current “ideas and influences.” The text of the blog is below. Please visit Two Coats for the full post with images.

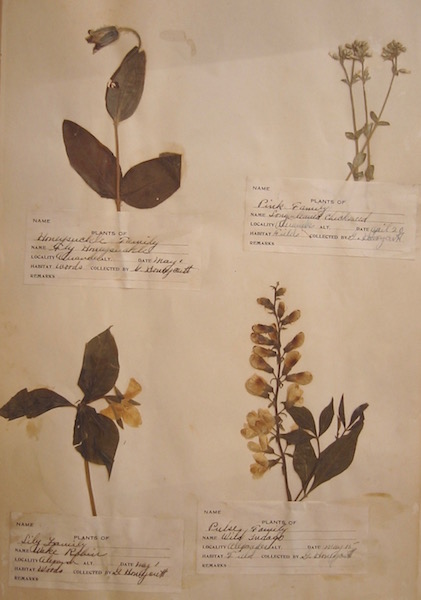

page from my grandfather’s herbarium

“Artist and citizen naturalist Brece Honeycutt lives in Massachusetts, on a colonial farmhouse in the foothills of the Berkshire mountains. Fascinated with the history of her home and the surrounding land, she reads handwritten antique diaries at the local library, gathers old textiles, and creates natural dyes from the plants she collects on her morning walks. During her walks, she closely observes changes to the landscape, making notes that become the basis for new projects. On the occasion of her solo show at Norte Maar, Honeycutt has compiled the following list of ideas and influences that inform her work.”

1. Henry David Thoreau. “It will take half a lifetime to find out where to look for the earliest flower,” noted Henry David Thoreau in his journal. [1] For seven years (1851-1858), Thoreau walked his environs around Concord, MA and recorded his observations noting when plants sprouted, trees leafed out, and birds returned. An inspiration for us all to be become Citizen Naturalists.

2. Citizen Naturalist. Recently I started participating in the USA National Phenology Network as a Citizen Naturalist, using Nature’s Notebook app. Phenology, as defined by the Merriam-Webster dictionary, is “a branch of science dealing with the relations between climate and periodic biological phenomena (as in bird migration or plant flowering).” In fact, Thoreau’s findings have become the basis for comparative studies being conducted by the scientist Dr. Richard B. Primack that demonstrate climate change and how the warming of the planet is affecting the cycles of our environs. Daily I note the returning ducks and birds, the flowering coltsfoot and the occasional spotting of a bobcat.

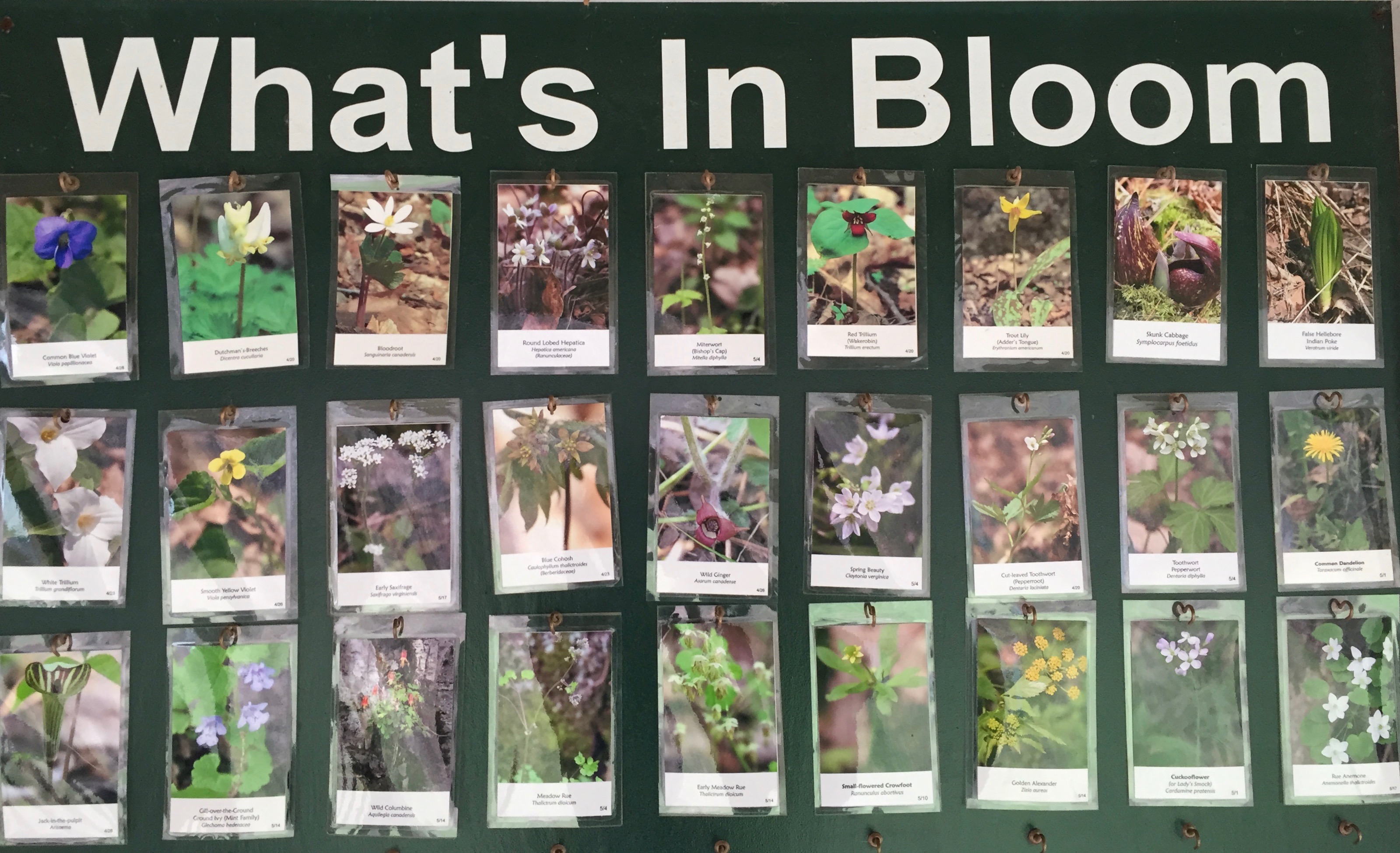

3. Emily Dickinson. Like Thoreau, Emily Dickinson was a keen observer of plants and a magnificent gardener. I wondered what plants were found in her area of Massachusetts in the 1800s and might we have them here? Dickinson wrote to her friend, Mrs. A. P. Strong, in 1848, “The older I grow, the more I do love spring flowers. Is it so with you? While at home there were several pleasure parties of which I was a member, and in our rambles we found many and many beautiful children of Spring, which I will mention and see if you have found them–the trailing arbutus, adder’s tongue, yellow violets, liver leaf, bloodroot and many other small flowers.” [2]

4. Spring Ephemerals. Indeed, all but the trailing arbutus are found on the grounds of Bartholomew’s Cobble (Ashley Falls, MA). In a few weeks, the Spring Wildflower Festival will begin at the Cobble and for the second year, I will be leading tours. I am busily reviewing my notecards, guidebooks and poems that I will read to the guests. The most important “tool” is to go and walk the trail, slowly, ever so slowly. Stopping, and really looking around. As Thoreau noted, the earliest flowers are the hardest to find. Spring ephemerals–plants that grow for a short time span due to the intense sunlight and the particular soil found at the Cobble–are fleeting and glorious. This year I want to embark on a project, “To know you is to draw you.”

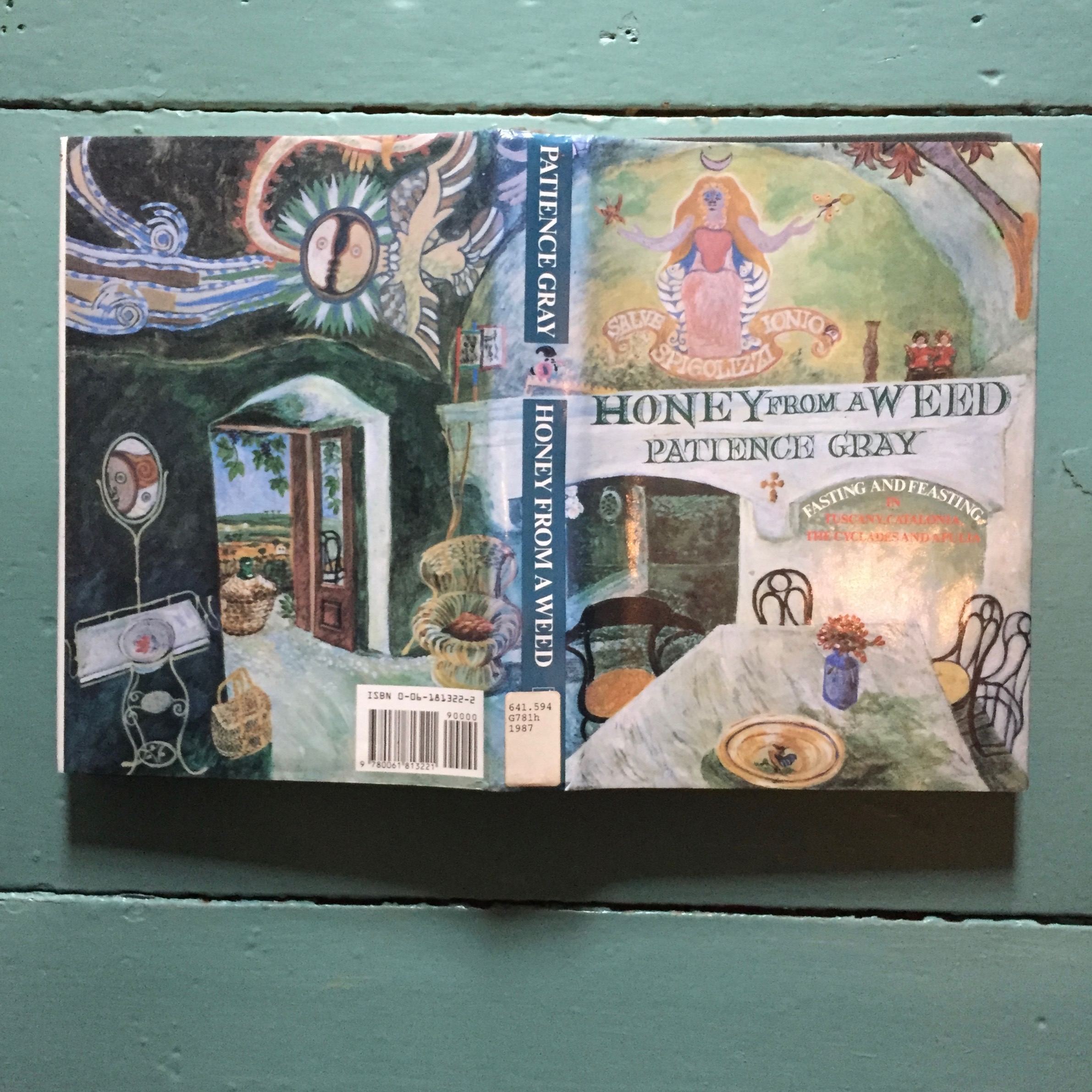

5. Herbariums. Plants & Place, Deerfield. What did that particular plant look like when it first sprouted? Gardeners, Citizen Naturalists like Dickinson and Thoreau made Herbariums to both identify and document their native flora and fauna. Each year, I vow to start my own Herbarium and to jump start this year’s process, I look forward to the upcoming symposium at Historic Deerfield–Plants and Place: Native Flora of Western Massachusetts. We will review various herbaria, including the early collected plant pages of Stephen West Williams.

6. Susan Howe. I had the pleasure of attending a lecture at The Morgan Library with Susan Howe and Marta Werner regarding the current exhibition I’m Nobody! Who are you? The Life and Poetry of Emily Dickinson. The exhibition catalog is a treasure trove of essays and images including a conversation between Werner and Howe, “Transcription and Transgression.”

Werner asks Howe about seeking “small, out-of the way archives.”

Howe responds: “Yes, I also enjoy small local libraries. Usually they have local historical collections where you will find things that historicists have neglected, or you find an old book with the odd spelling from seventeenth century. I don’t know. It’s the peace found in the landscape of place.” [3]

7. Webster’s Dictionary. Howe discussed also that Dickinson used a particular dictionary, Noah Webster’s 1844 An American Dictionary of the English Language. In a post-lecture conversation, Howe said that not only were Dickinson’s words defined by this exact dictionary, but that her gaze across the pages of the dictionary influenced her writings. I procured a facsimile 1828 Webster (also found in the Dickinson home) and have been looking up words found in her poetry, Thoreau’s writings and even to see if a spring ephemeral can be found on the pages of this book, evidencing that a plant was very much in residence. What a treat to read Jennifer Schuessler’s article “A Journey into the Merriam-Webster Word Factory” in the March 22 edition of the New York Times.

8. Mending. Sewing. Georgia O’Keeffe. Alabama Chanin. The current exhibition Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern at the Brooklyn Museum charts her life through drawings, paintings, photographs and clothing. Her friend Anita Pollitzer noted that O’Keeffe was “extremely industrious, her hands are seldom idle. She loves to sew—not fancy things, but Chinese silk blouses and loose clothes that become her.” One wall label noted her to be a “conscientious mender” of clothes.

Inspired by Alabama Chanin a few years ago, I found the determination to make some of my own clothes. Stitch by stitch.

9. Clean Air. Clean Water. Rachel Carson. Where will we be without clean air and clean water? After watching PBS’s documentary American Experience: Rachel Carson, I sought the pages of Silent Spring, first published in 1962. Carson’s intensely factual, yet lyrically written, scientific book exposed the devastation occurring from the use of synthetic chemicals on all living beings.

Carson states:

“If the Bill of Rights contains no guarantee that a citizen shall be secure against lethal poisons distributed either by private individuals or by public officials, it is surely only because our forefathers, despite their considerable wisdom and foresight, could conceive of no such problem.

“I contend, furthermore, that we have allowed these chemicals to be used with little or no advance investigation of their effect on soil, water, wildlife, and man himself. Future generations are unlikely to condone our lack of prudent concern for the integrity of the natural world that supports all life.” [4]

10. Wendell Berry. Now. Wendell Berry asks us to remain in the present with our actions in regards to climate change and land abuse. He posits that if we are only thinking of what can be accomplished in the future, we are missing the opportunity for what we can do right now. He invites us to “save energy now for the future” by beginning with small acts today. Berry states,

“….so few as just one of us can save energy right now by self-control, careful thought, and remembering the lost virtue of frugality. Spending less, burning less, traveling less may be relief. A cooler, slower life may make us happier, more present to ourselves, and to others who need us to be present.” [5]

Footnotes:

[1] Henry David Thoreau, Thoreau’s Wildflowers, edited by Geoff Wisner, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), pg. 16.

[2] Emily Dickinson, The Letters of Emily Dickinson, 1845-1886, Google Docs, page 38.

[3] Susan Howe and Marta Werner, “Transcription and Transgression,” The Networked Recluse: The Connected World of Emily Dickinson, (Amherst: Amherst College Press, 2017), pg. 135.

[4] Rachel Carson Silent Spring, (Greenwich: Fawcett Books, 1962), pg. 22.

[5] Wendell Berry, Our Only World Ten Essays, (Berkeley: Counterpoint, 2015), pgs. 174, 175.

“bewilder: New Work by Brece Honeycutt,” Norte Maar, Cypress Hills, Brooklyn, NY. Through April 23, 2017.