of colors & moons

flipping flapping through days & pages of moths & butterflies of collage & happenstance of colors & moons

Books |

flipping flapping through days & pages of moths & butterflies of collage & happenstance of colors & moons

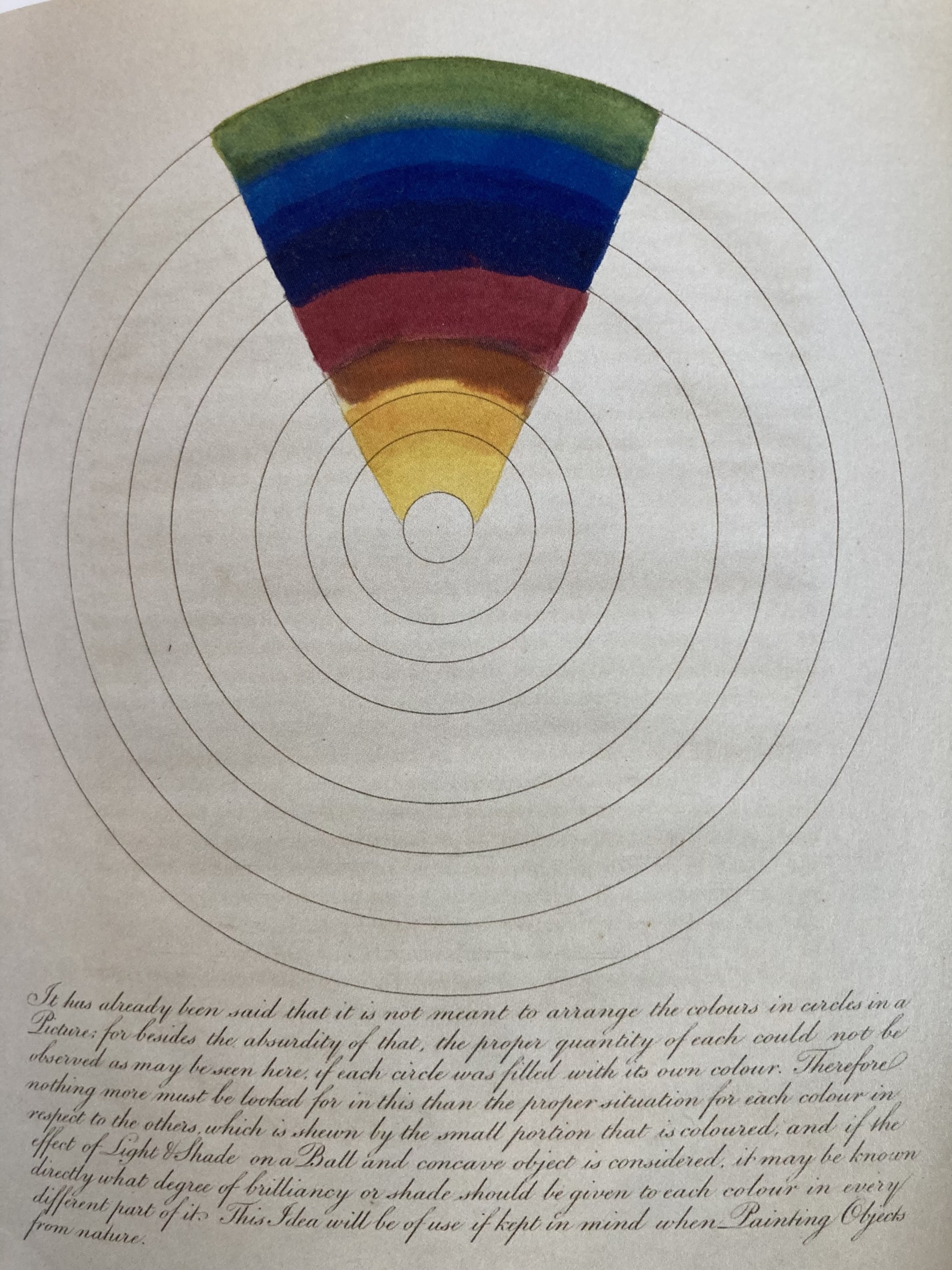

yesterday’s bright studio light, catching color out of the corner of my eye. preparing for DFZ Gartside discussion reading poetry for the Slade Colour & Poetry symposium mapping out a poetry manuscript with Poetry Forge colour or color no matter how you spell it connects the dots

Rainbows In dye swatches In color torn from pages On wooden spools of thread Research materials for Poetry manuscript class- A Body of Work- with Poetry Forge

White Yellow Orange Scarlet Green Blue Crimson Violet

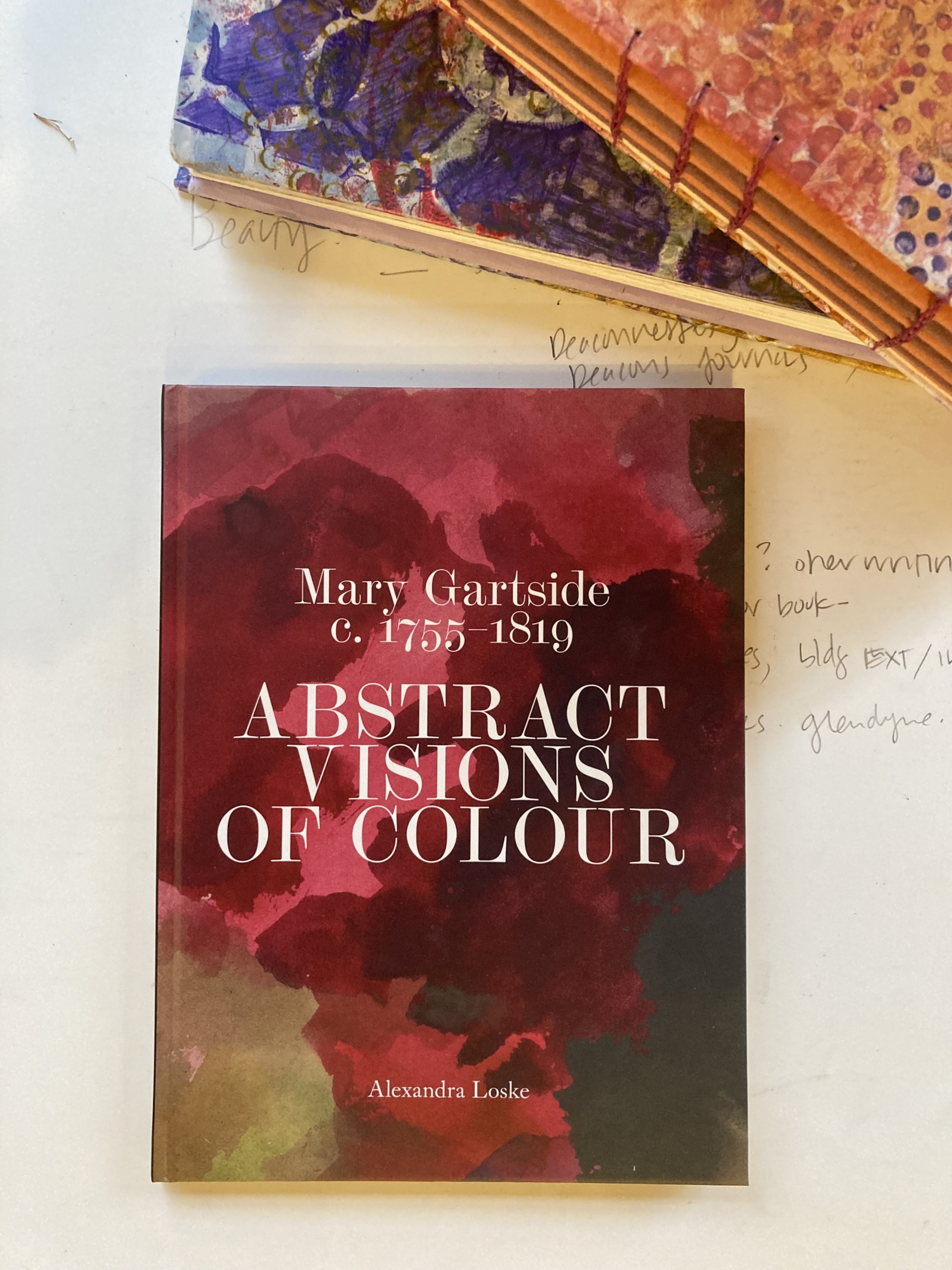

Find more information on Alexandra Loske and her colour research, here. Mary Gartside (c.1755-1819) Abstract Visions of Colour published by Thomas Heneage Art Books

morning collage/watercolor responding to the objects on my table Geoff Young chap book paste paper folder tangled threads or the grey outside

greyed: palest grey to white violet grey pink cosmos grey violets dropped in milk grey a drop of cobalt blue grey orangesicle ice cream grey sunpoked through yellow grey old yellowed newspaper grey grey green sky portends rain

writing, so often a silent act-

thwack

opening a folder

filled with poems ready

for A Body of Work manuscript workshop

with Poetry Forge

A huge thank you to Suzi Banks Baum and Arrowmont School for the invitation to participate in the writers’ studio at Pentaculum 2024.

“The human eye can perceive over a million different varieties of color, but the human brain has better things to do than name them all.” “Newton segmented the spectrum into just seven named colors: the classic ROY G BIV divisions.” “While this might have seemed arbitrary, much later research by anthropologists concluded that most cultures at least have names for black, white, red, green, yellow and blue: six basic color terms typically in that order, as if there were an innate hierarchy.”

[ from Neil Parkinson, “The History of Color: A Universe of Chromatic Phenomena”]

90,000 artifacts (textiles, ceramics, furniture, ironwork….) 20,000 American & European imprints 3,000 record groups of manuscripts, trade cards, photographs, ephemera 7,500 plant specimens 1,000 acres

+Specialists, Conservators, +Librarians, Archivists, +Curators, Gardeners, +Scientists, Fellows “Research is a material” and earlier this year, as a Maker-Creator Fellow, I explored Winterthur's Shaker collection (and others) and loved every second of researching, working with archivists, conservators, curators, fellows and librarians; and walking on their incredible grounds. Artists & Makers consider applying for Winterthur’s Maker-Creator Fellowship! Happy to answer any questions. Applications due 1/15/2024 Application info right HERE

This past week, Sarah Margolis-Pineo, Curator at Hancock Shaker Village and I went on a field trip to meet our collaborator at Camphill Village for a tour. It wasn’t the astoundingly beautiful and plentiful herb garden or creative energy found in the neat stacks of bound books and elaborate calligraphy that took my breath away (and believe me they did), but the three essentials that Camphill is founded on.

Three Essentials

1—Recognition that in every human being lives an eternal healthy spirit no matter the disability.

2—Every human being has the right and responsibility to learn and develop.

3—Continuous striving to create community.

And so, we provide our summer reading list.

Summer brings us out into the garden and woods, appreciating nature’s daily changes and honing in on all the residents, both flora and fauna. Early mornings before working in the garden and rainy afternoons are spent reading to become more “plant-conscious,” as author Richard Powers terms it.

——————————————————————————————————————

The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming by David Wallace-Wells (Tim Duggan Books, 2019).

“Personally, I think that climate change itself offers the most invigorating picture, in that even its cruelty flatters our sense of power, and in so doing calls the world, as one, to action. At least I hope it does. But that is another meaning of the climate kaleidoscope. You can choose your metaphor. You can’t choose your planet, which is the only one any of us will ever call home.” (pp. 228-9).

Casting Deep Shade by C. D. Wright (Copper Canyon Press, 2019)

Ben Lerner writes in the introduction, “It is a book full of love and admiration for eccentric arborists and purveyors of folk knowledge, for they are—like the poet—committed to keeping the language and landscape particular, unpredictable, collective. Committed to preserving these slow-growth kinetic sculptures [beech trees] under siege by profiteers and voles. This is an uncommonplace book.” (p. x)

“Journal of Medicinal Plant Conservation,” A United Plant Savers Publication (United Plant Savers, 2019).

“The Theme is Voices from the Land, with intent to share indigenous perspectives in relationship with plants. This perspective is most profound in the article on white sage and the conflict with commercialization and cultural appropriation of a plant sacred to many…”We have filled this issue with international perspectives on how medicinal plants are managed, such as the innovations in Bulgaria and the impact of communism in regards to the medicinal plant trade in Albania…”In a rapidly changing environment we have a story from the Marshall Islands dealing with climate change, the opportunity of using invasive plants as medicine…”Stories from our Botanical Sanctuary Network and featured artists from our Deep Ecology Art Fellowship bring creativity to how we can enrich our relationship with plants and in return heal ourselves and the planet.” (p. 2)

The Art and Science of Natural Dyes: Principles, Experiments and Results by Joy Boutrup and Catharine Ellis (Schiffer Books, 2018)

“For millennia, humans perceived color through nature and its reflections in human interpretation. Throughout the ages and around the world, dyers relied on the colors obtained from plants, fungi, lichen, insects, shellfish, and rock minerals…”We want to understand how dyes and mordants work and how different types of fibers react to dyes, mordants, tannins, water, heat and ulturviolent rays…”Having very clear and precise instructions to follow helps us achieve that goal, but unless we understand the whybehind the how, we won’t be able to make the most intelligent decisions when changing circumstances require that recipes be altered…”Taking such factors into account, this book creates a bridge between art and science, showing us the way.” (p. 8).

Shaker Herbs: A History and A Compendium by Amy Bess Miller (Clarkson N. Potter, 1976).

“An anonymous Shaker editor of the medicinal herb catalog published by the New Lebanon society gave his readers a bonus—a “supplementary” in 1851 which today would be termed a preface. This was the first time such a statement appeared in a Shaker medicinal marketing publication. It reflects the reasons the Shakers felt so much care and effort should go into the production of medicinal products:

“Perhaps no study contributes more to the length, utility, and pleasure of existence—which adds to health, cheerfulness and enlarged views of creative wisdom and power, and which improves the morals, tastes and judgment, more than the science of botany.” (p. x).

A Life Made by Hand: The Story of Ruth Asawa by Andrea D’Aquino (will be published in early September by Princeton Architectural Press).

“Ruth looked carefully at everything around her.

“What kind of plant are you? she wondered.“

“What a fascinating shape your shell is, Snail.”

“Hello Spider.

How did you figure out how to make your web?”

“Ruth liked to look at the drops of water in her garden.

She often stopped to notice how the light shone through their delicate shapes.”

——————————————————————————————————————–

Trees. Plants. Dyes. Herbal Medicines. Hands. And only one Earth.

Summer promises the great outdoors: time to explore new terrains or become more familiar with the world found on your doorstep. As a primer to our summer exploration, we have been delving into ‘nature based’ reading.

on a colonial farm’s recommended summer reading list:

Carlos Magdalena, The Plant Messiah: Adventures in Search of the World’s Rarest Species, (New York: Doubleday, 2017), pg. 6.

“I want to make the world aware of what plants do for us. I want us to give plants a value and appreciate what they do. I want us to understand their importance for our survival and the survival of our families—our babies, grandparents, and future generations. I want us to realize that without them we would die, and most living things on land in the air would die with us. I want us to be enthused by the importance of conservation, to be fired with determination that we should never give up, even if there is only one plant left in the world. I want us to understand the importance of plants so much that we are moved to do something about it.”

Diana Beresford-Kroeger, The Global Forest 40 Ways Trees Can Save Us, (New York: Penguin Group, 2010), pg. 69.

“But art has a sister. The sibling is science. Art and science are of the same house, of the same family. Art in all its forms opens the way for science, because art is the precursor to science in all things. Art sounds the bell of change that leads to discovery, and science runs in to listen, to test, and to learn. Art sometimes molds and other times reflects the thoughts of culture and then defines the tides of fashion. Science follows in the wake of those tides and looks back at the great fetch of “why” to derive the question “how.”

“There is some time left. There is time for a different way of thinking in which man can rethread the needle and sew a life for the future. For if nature is destroyed, art will stand still and the creativity of science will follow suit. “

Tristan Gooley, The Lost Art of Reading Nature’s Signs, (New York: The Experiment, 2010), pg 3.

“Picking up one simple scent can take the mind on an extraordinary journey. Sense and thought, observation and deduction, this two-step process is the key to transforming a walk from mind-numbing to synapse-tingling. One cannot work without the other; the brain can build wondrous edifices in our mind but it requires the scaffold that our senses provide.”

Richard Powers, The Overstory, (New York: W.W. Norton, 2018), pgs. 454-455.

‘ “Trees stand at the heart of ecology, and they must come to stand at the heart of human politics. Tagore said, Trees are the earth’s endless effort to speak to the listening heaven…..If we could see green, we’d see a thing that keeps getting more interesting the closer we get. If we could see what green was doing, we’d never be lonely or bored. If we could understand green, we’d learn how to grow all the food we need in layers three deep, on a third of the ground we need right now, with plants that protected one another from pests and stress. If we knew what green wanted, we wouldn’t have to chose between the Earth’s interests and ours. They’d be the same.” ‘

Andrea Barnet, Visionary Women: How Rachel Carson, Jane Jacobs, Jane Goodall and Alice Waters Changed Our World, (New York: Ecco, 2018), pg. 330.

“People ask how can I as one person can make a difference……But if we can start making considered choices in our everyday actions, the little things – what we buy, what we wear, if we think carefully about the consequences of these choices – how it was made, where did it come from, was it child slave labor, was it cruelty to animals, etc., then we can start making different choices. Small choices. But multiply these small choices by a hundred, a thousand, a million and then a billion and then you start to see a different kind of world.” Jane Goodall.

I will be tucking wildflower, bird and trees guides into my bag this summer, along with newly handmade books to start mapping what I see, hear and smell around the farm. Delving deeper into where I live and what lives around me, guided by the thought that all is connected, and that by our choices we can make a difference.

[Note: Click on Author’s name for their website, including Carson, Jacobs, Goodall and Waters.]

We eagerly await the arrival of spring, more so this morning as snow flakes floated down to outline branches, leaves and stone walls as only newly fallen snow can do. We’ve had a few warm days sprinkled here and there in the past few weeks, but not enough to truly turn the corner and bring on full spring.

Saturday marks the start of the Spring Wildflower Festival at Bartholomew’s Cobble, as well as my third year as a wildflower guide there. On bitterly cold Saturdays in March, we guides gathered to discuss the geology of the site, the area’s ecology and the associated plant botany. We trudged through ice and snow over the trails, imagining the emergence of the green shoots and later lacy spring flowers. Bartholomew’s Cobble is a National Natural Landmark and we owe the rare diversity of the plant life to geological action that occurred 420 million years ago that results in both quartzite (acid) and marble (base) existing side by side–not a normal occurrence.

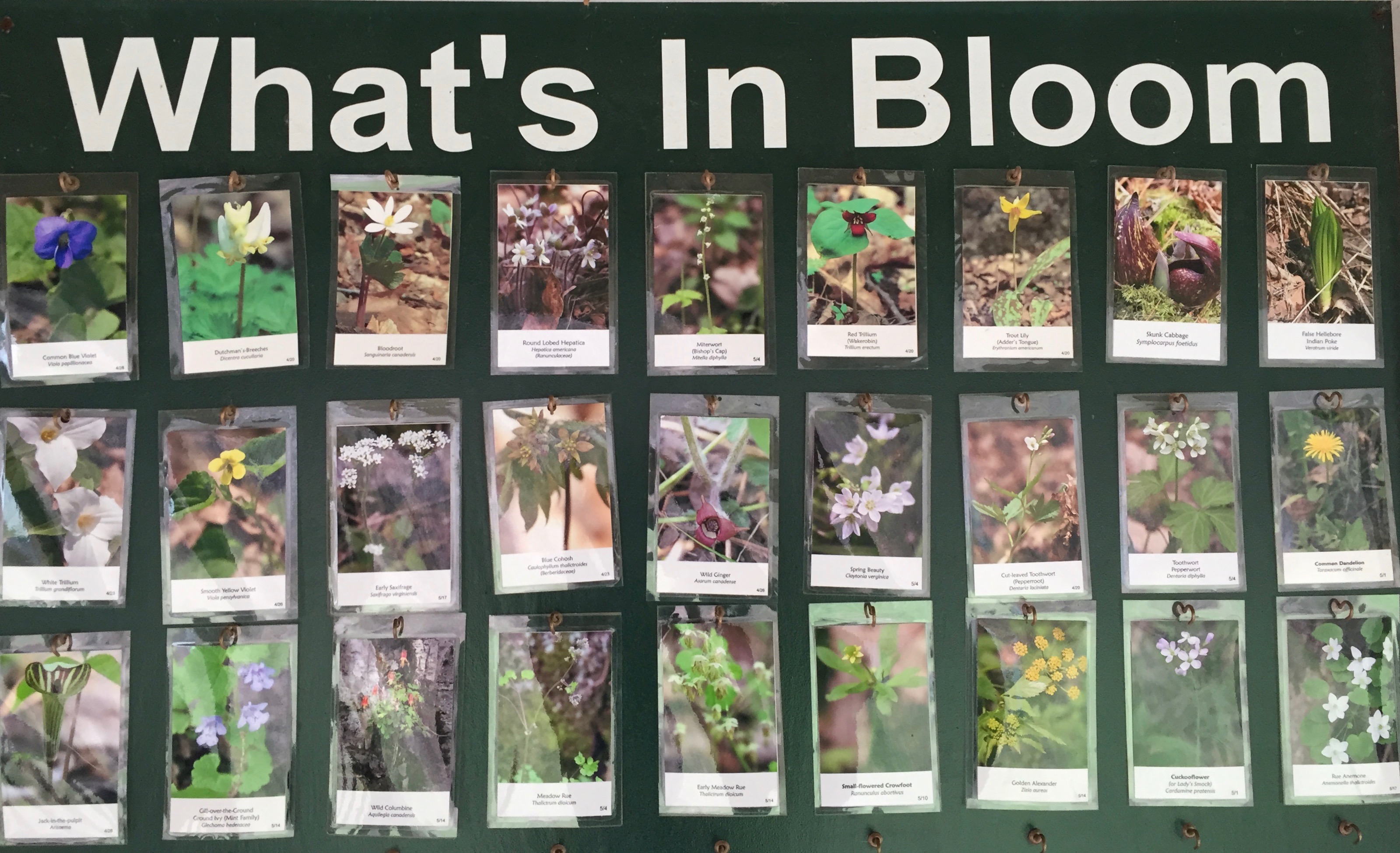

The “What’s In Bloom’ board at Bartholomew’s Cobble from May 2017

In preparation for my walks, I delve deeply into each plant’s characteristics, but I also search for the writings of others that found fleeting ephemerals.

Emily Dickinson, gardener and poet, reports of an 1848 spring walk to her friend Abiah Root:

“There were several pleasure parties of which I was a member, and in our rambles we found many and many beautiful children of Spring, which I will mention and see if you have found them — the trailing arbutus, adder’s tongue, yellow violets, liver leaf, bloodroot and many other small flowers.” 1

Mary Oliver recounts slipping away from school one spring day:

“I walked, all one spring day, upstream, sometimes in the midst of ripples, sometimes along the shore. My company were violets, Dutchman’s-breeches, spring beauties, trilliums, bloodroot, ferns rising so curled one could feel the upward push of the delicate hairs upon their bodies…The beech leaves were just slipping their copper coats; pale green and quivering they arrived into the year. My heart opened, and opened again. “2

On April 3, 1853 , Henry David Thoreau notices one of spring’s smallest flowers:

“To my great surprise the early saxifrage is in bloom. It was, as it were, by mere accident that I found it. I had not observed any particular forward news in it, when happening to look under a projecting rock in a little nook on the south side of a stump I spied one little plant which had opened three or four blossoms high up the cliff. Evidently you must look very sharp and faithfully to find the first flower. Such is the advantage of position.”

Bartholomew’s Cobble rightly boasts about its spring ephemerals and many noted and seen by Dickinson, Oliver and Thoreau—adder’s tongue, bloodroot, blue cohosh, Dutchman’s-breeches, fringed polygala, Jack-in-the-Pulpit, liver leaf, spring beauty, rue anemone, trillium, saxifrage, wild columbine, and violets are there, for example. Stop by on Saturdays and Sundays for guided tours, or ramble on the Ledges trail on your own with eyes wide open. As Oliver notes, “Attention is the beginning of devotion.”4

1, Judith Farr, The Gardens of Emily Dickinson, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004), pg.97.

2. Mary Oliver, Upstream, (New York: Penguin Press, 2016), pgs 4-5.

3. Geoff Wisner, Thoreau’s Wildflowers, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), pg. 16.

4.Oliver, pg. 8

Note: I will be leading tours on April 21 at 12pm, April 22 at 10pm and May 13th at 3pm. There are guided tours on Saturday and Sunday, 10am, 12pm, 2pm & 3pm. Bartholomew’s Cobble, 105 Weatougue Road, Ashley Falls, Sheffield, MA.

Second Note: A documentary about Emily Dickinson, Seeing New Englandly will be shown at the Roelieff Jansen Community Library on April 28 at 4pm, 9019 Route 22, Hillsdale, NY.