I stand at my worktable, pierce holes in paper, thread a needle with waxed linen and bind the pages together forming a hand bound book. My actions are not revolutionary, but they are meditative, and ones that fellow bookbinders have done for centuries.

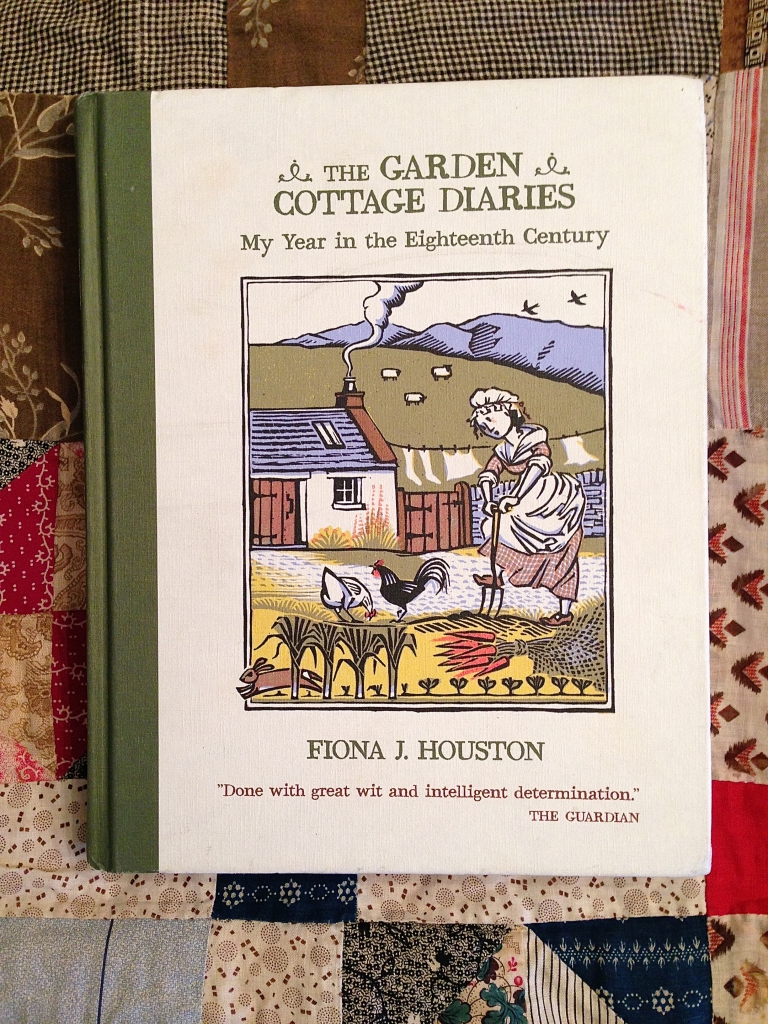

As I line up the pages within the eco-dyed covers, and rhythmically slip the needle through the holes, my mind wanders to images of leaves of books, of books within books. Often books are about just that – other books – and with more regularity now, images of archival manuscripts are reproduced therein. Thankfully so, for these manuscripts are hidden from view, tucked away in special (often secure) rooms in libraries for safe-keeping.

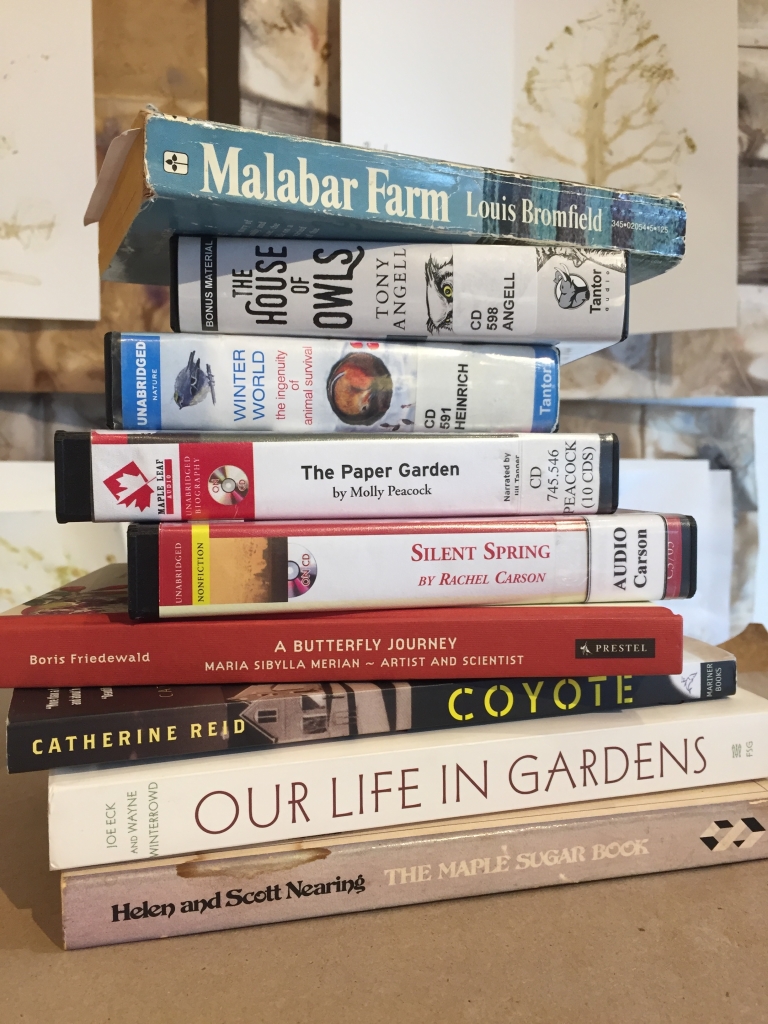

eco-dyed covers ready for binding

Scholars, poets, artists and authors search out these handmade objects, for the energy and information that they hold within. A tactile experience described by Jill Lepore:

“…sitting in that archive, holding those sheets of foolscap stitched together with the coarsest of threads, I began to think that Benjamin Franklin’s sister had something to say after all, something true, something new. Very delicately, I once more turned the brittle pages of the Book of Ages, and in them I saw an unwritten story: a history of books and papers, a history of reading and writing, a history from reformation to revolution, a history of history. This, then, is Jane Franklin’s story: a book of ages about ages of books.”

Lepore’s biography of Jane Franklin (Benjamin Franklin’s sister) revolves around this manuscript housed in the New England Historic Genealogical Society. Franklin “…stitched four sheets of foolscap between two covers to make sixteen pages. On its first page, she wrote, “Jane Franklin Born on Monday March 27 1712″. She called it her Book of Ages.” Lepore charts the course of her biography using Franklin’s book as the route; the strokes of Franklin’s quill pen in her handmade book provide the coordinates.

Step back. Examine the pen strokes, their placement on the page, the materiality of the paper, as Susan Howe wisely advises in her recent book, Spontaneous Particulars: The Telepathy of Archives, when examining Jonathan Edwards’ papers at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University.

“Three of Edwards’ manuscript books I particularly love are titled Efficacious Grace. Two of them he constructed from discarded semi-circular pieces of silk paper his wife and daughters used for making fans. If you open these small oval volumes and just look—without trying to decipher the minister’s spidery script, pen strokes begin to resemble textile thread-text. Surface and meaning co-operate to keep alive in one process mastery in service, service in mastery.”

“Spidery,” and “lavish, calligraphic…slender, artful”, are adjectives used to describe the styles of Edwards and Franklin, respectively. Paper made from rags (Franklin) and silk (Edwards) bound by their hands and holding the words written in their hands. These manuscripts are more than books; they are also a portal into an historic figure and a corresponding era.

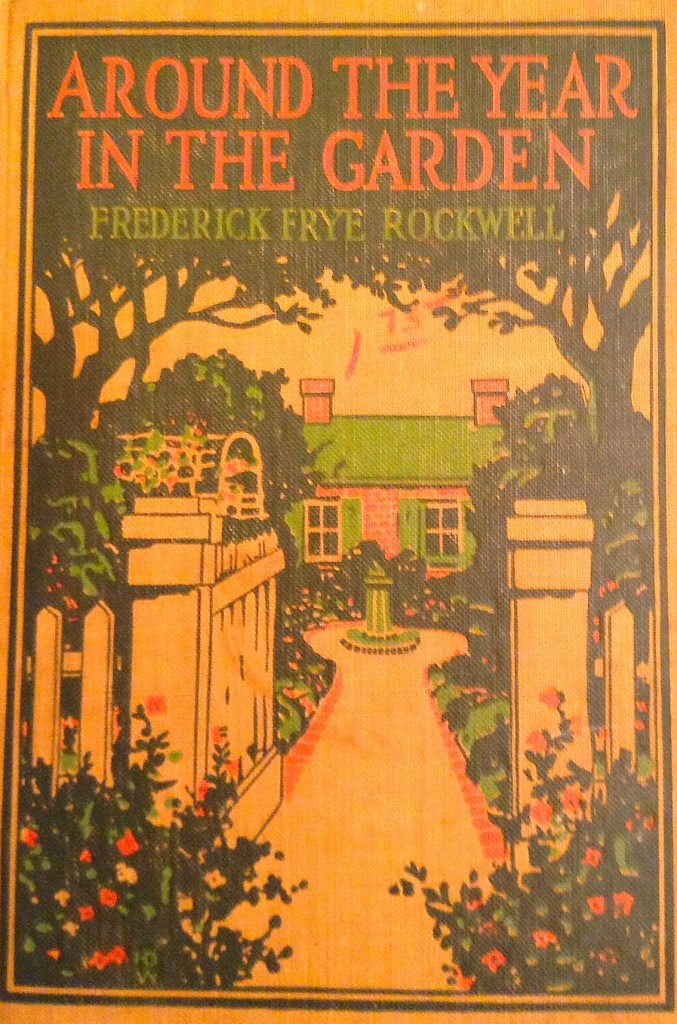

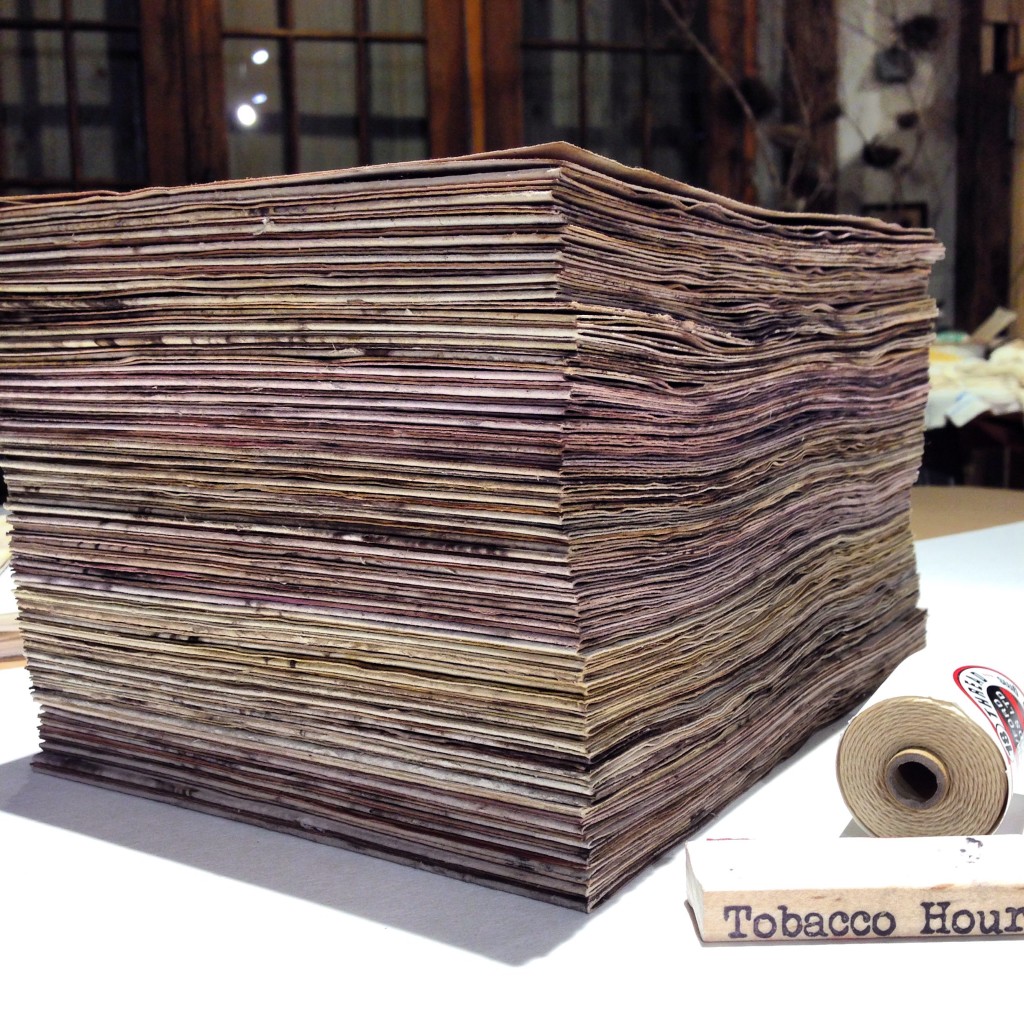

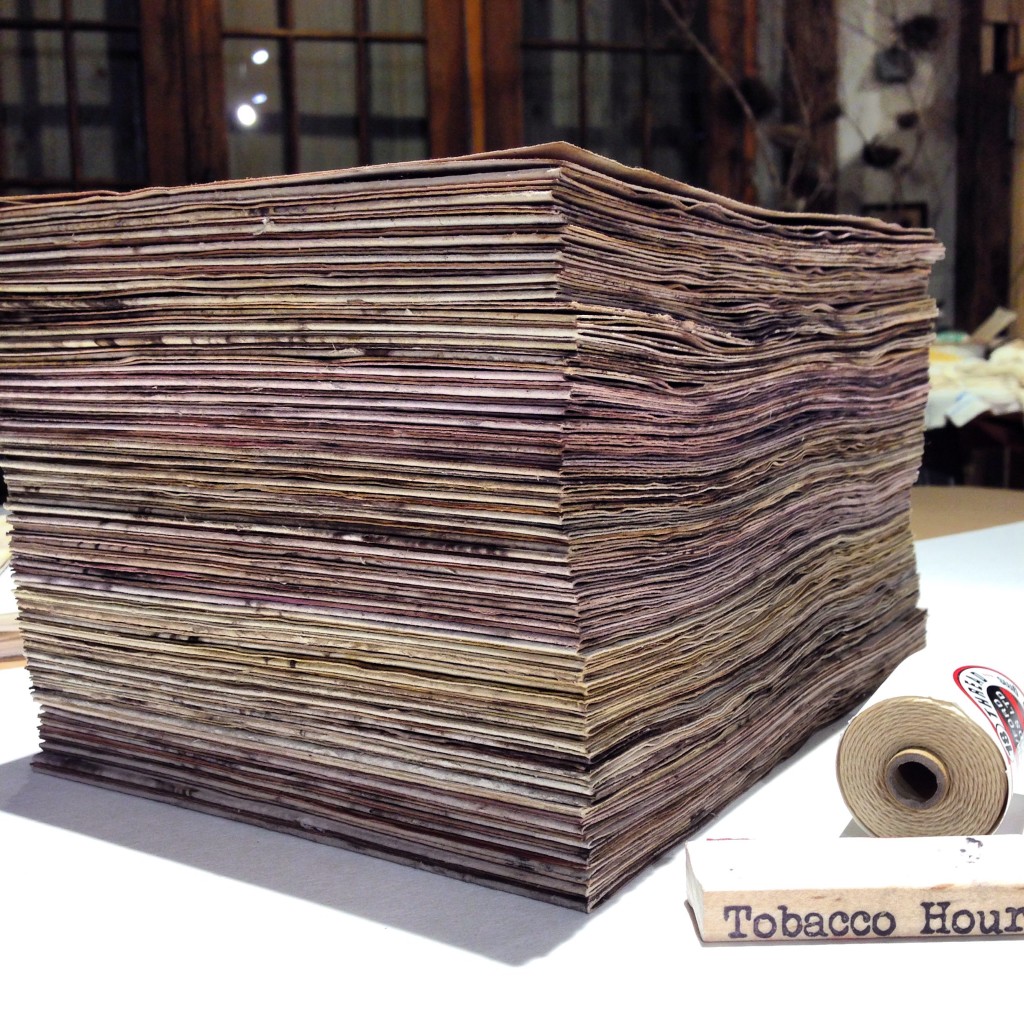

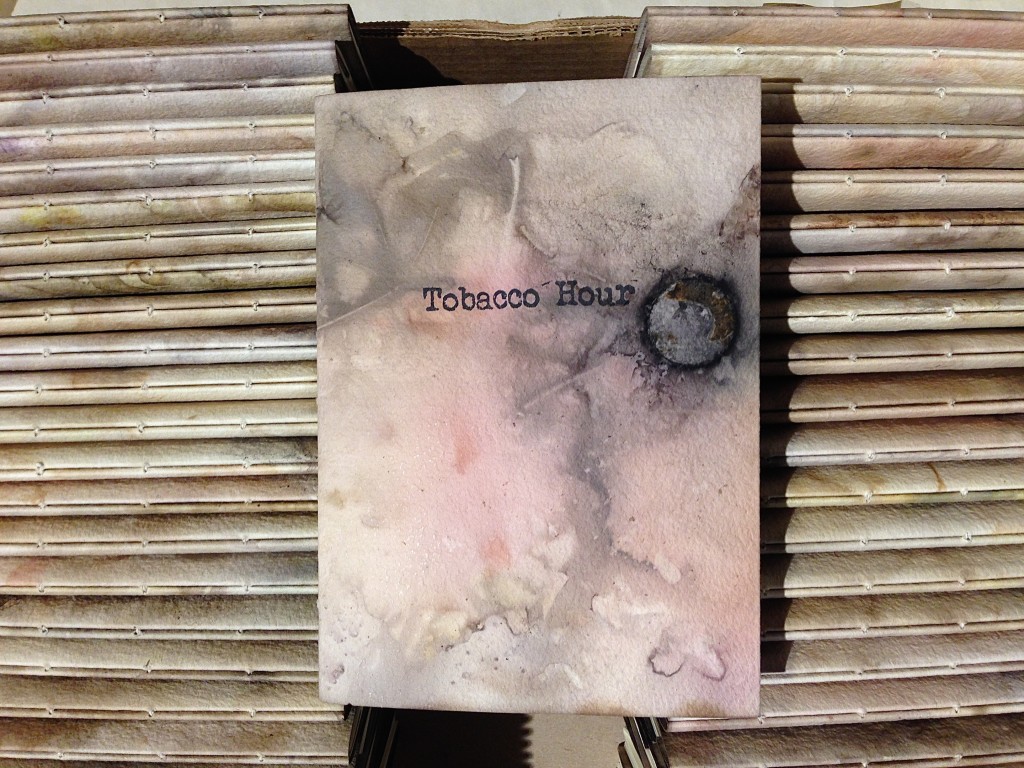

bound copies of Tobacco Hour

Objects. A few weeks ago, the poet Susan Howe delivered her lecture (from which the above referenced book is based) at The Hotchkiss School in conjunction with the exhibition, “Hotchkiss in 50 Objects” at the Tremaine Art Gallery. The exhibition traced, defined and referenced Hotchkiss’ history by way of fifty items from the school’s archives. Before she began her lecture, Howe told us that while giving her talk, a series of images would be shown, but she would not stop to tell us what each was, rather they would roll forward as a “collage”. Images of documents, book pages and fragments floated by on the screen, and we connected the dots by way of her multi-faceted details. Howe states:

“In research libraries and collections, we may capture the portrait of history in so-called insignificant visual and verbal textualities and textiles. In material details. In twill fabrics, bead-work pieces, pricked patterns, four-ringed knots, tiny spangles, sharp-toothed stencil wheels; in quotations, thought-fragments, rhymes, syllables, anagrams, graphemes, endangered phonemes, in soils and cross-outs.”

Find some paper and thread, make a book, and begin writing down details.

Objects.

Jill Lepore, Book of Ages: The life and Opinions of Jane Franklin, (Alfred Knopf, 2013), pgs. XIII-XIV, XII, 49.

Susan Howe, Spontaneous Particulars: The Telepathy of Archives, ( Christine Burgin/New Directions, 2014), pgs. 46, 21.

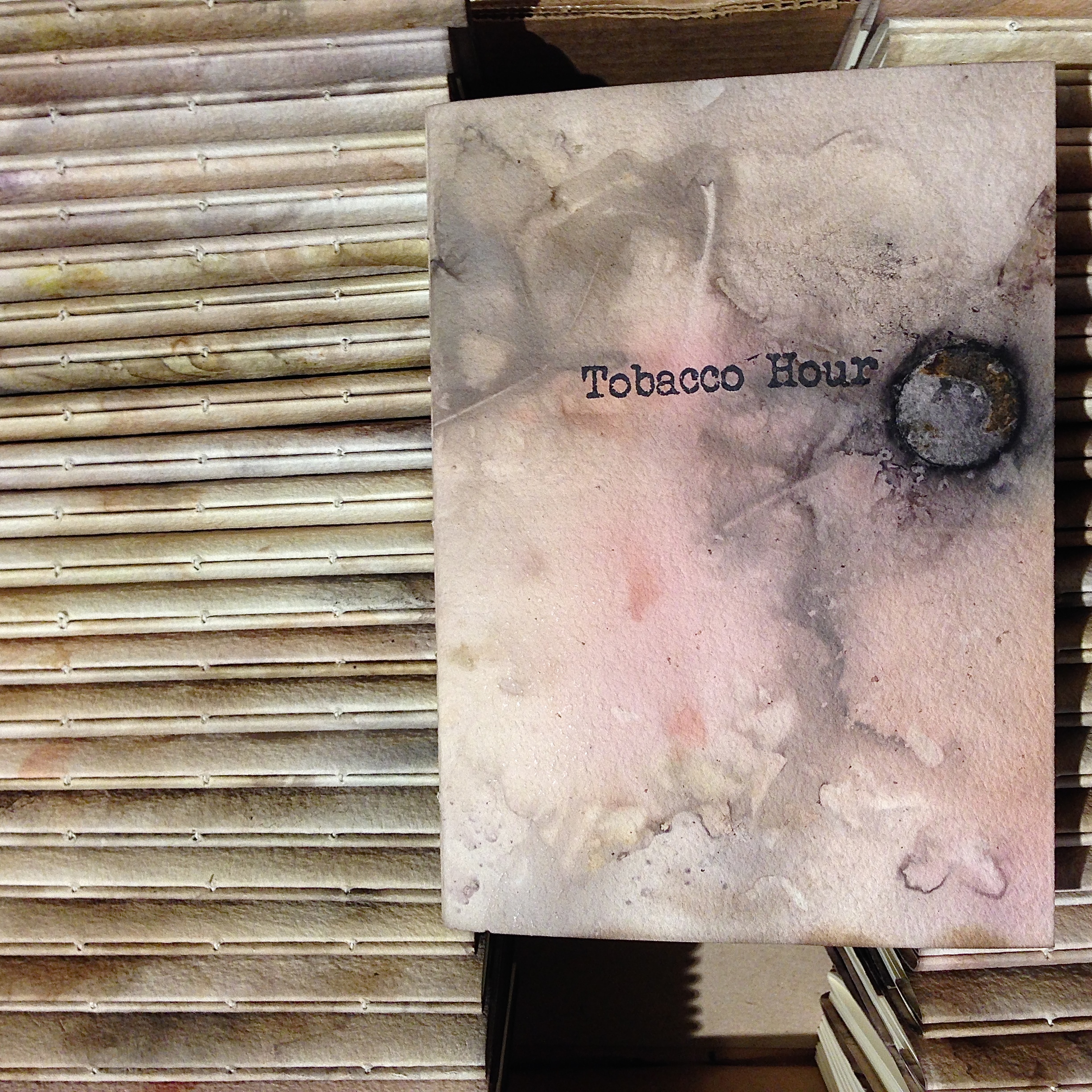

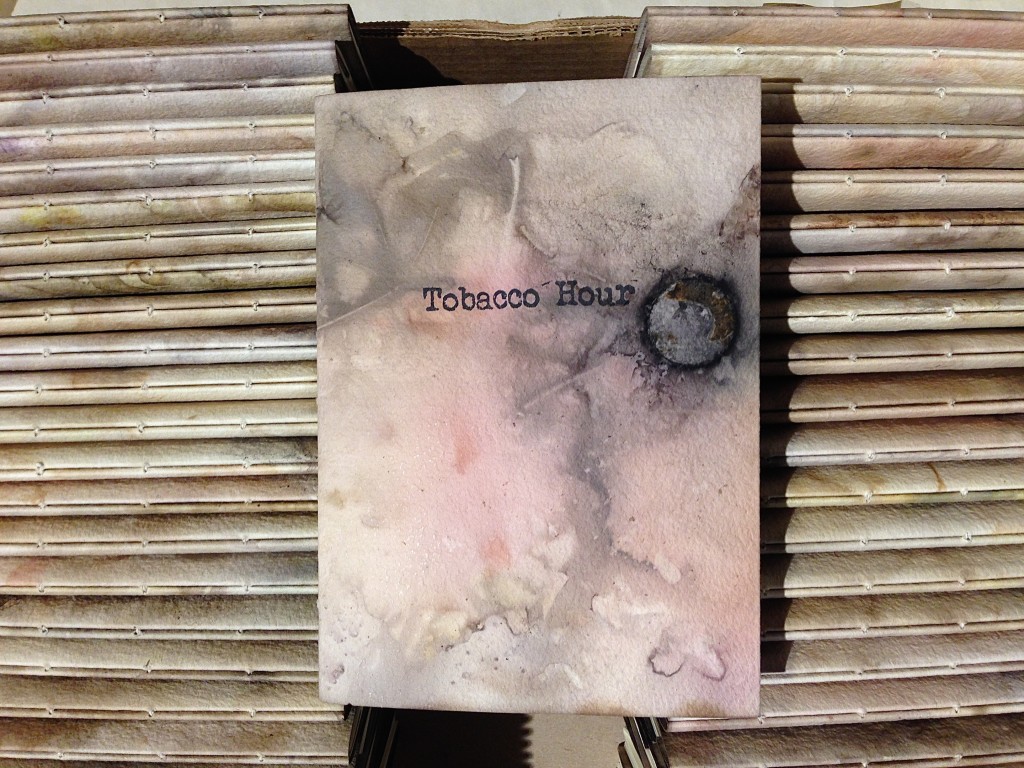

Note: Tobacco Hour a collaboration between poet/Dara Mandle, artist/Brece Honeycutt, and publisher/Jason Andrew/Norte Maar will be published in April 2015. Special thanks to Barbara Mauriello for her encouragement and consultation on the project.

sneak peak of Tobacco Hour cover