jill & jane

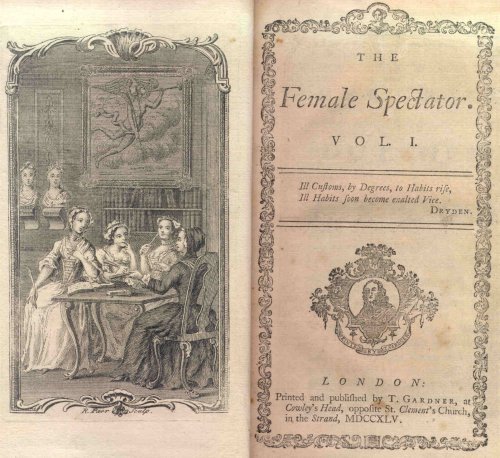

We can look forward to learning a great deal more about Jane Franklin (1712-1794) when Jill Lepore’s book The Book of Ages: The Life and Opinions of Jane Franklin is published this October. In the meantime, one can savor the recent article by Lepore in the July 8 & 15 edition of The New Yorker.

Jane was the sister of Benjamin Franklin and the person that he wrote the most letters to during his lifetime. Lepore stitches together Jane’s life – it’s “ordinariness” in spite of Jane being an obviously exceptional woman – from their lively correspondence as well as Jane’s unpublished “book”, described in the passage below:

“But she did once stitch four sheets of foolscap between two covers to make a little book of sixteen pages. In an archive in Boston, I held it in my hands. I pictured her making it. Her paper was made from rags, soaked and pulped and strained and dried. Her thread was made from flax, combed and spun and dyed and twisted. She dipped the nib of a pen slit from the feather of a bird into a pot of ink boiled of oil mixed with soot and, on the first page she wrote three words: “Book of Ages”—-a lavish, calligraphic letter “B”, a graceful, slender, artful “A”.”

The New Yorker’s digital edition gives one the chance to view pages from Jane’s Book of Ages and see her ‘calligraphic’ letters as she documents the arrivals, departures and marriages of her family.

“Book of Ages,” Jill Lepore

Lepore’s decision to write about Jane Franklin is quite personal, not only as revealed in her written article but also in the podcast: ‘Out Loud: Jane Franklin’s Untold American Story’.

If I could time travel, I would go back to the colonial days to talk with Jane and then move forward to October 2013, when I can hold Lepore’s biography of Jane Franklin in my hands.

The New Yorker, July 8 &15, Jill Lepore, “The Prodigal Daughter, Writing History, Mourning,“ The New Yorker, July 8 & 15, 2013, pgs. 34-40.