one year

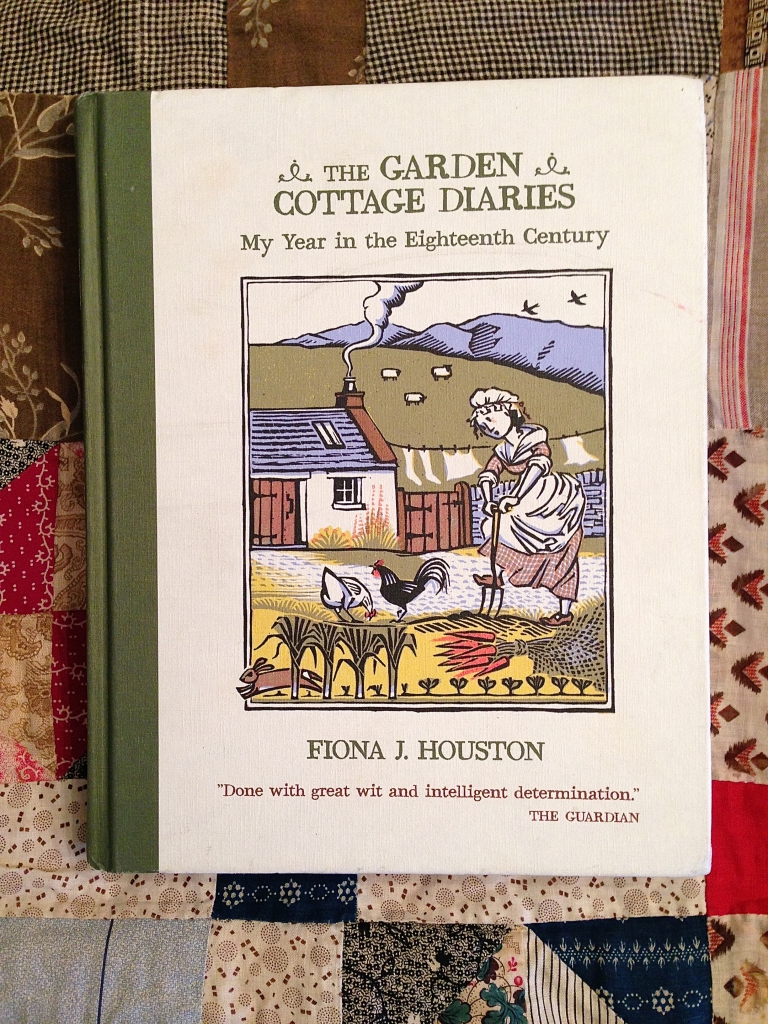

Imagine my delight at happening upon Fiona J. Houston’s book, The Cottage Diaries My Year in the Eighteenth Century. Why would someone choose to live for a year in a small house without running water, electricity, heat or any of the comforts that we are accustomed to? Ironically, the present led her back to the past. While investigating the history of Scottish food for an exhibition, she read Felicity Lawrence’s Not on the Label: What Really Goes into the Food on your Plate, and was shocked by the lack of nutrients found in industrialized food. She posited that people ate better in late eighteenth century Scotland and decided to take on the challenge of living and eating for a year as a dominie’s wife (a dominie is a Scottish schoolmaster).

Houston writes:

“One of my reasons for trying to go back in time was my anger at our throw-away society. It’s not just the wastefulness of buying goods, using them for a short time and then chucking them out that upsets me. It is the whole swathe of human activity and endeavour that is negated by this cycle. In the past, people had fewer resources. They had to use their skills and ingenuity to obtain the things that they needed for daily life. They had to make, mend, improvise and invent. I like all of that. I may not have all of the skills, but I have the inclination. In deciding to live simply for a year, I was setting myself a challenge to let the practical side of my nature come to the fore.”

Houston sets herself up in a small house and kits it to an eighteenth century standard with a simple table and chair, bed, a few candlesticks, pots and pans, and a range dating from 1860 (women of the prior century would have cooked on an open hearth, but the structure of Houston’s cottage did not allow for this). She wears clothing of the time (skirts and cloaks, both become soaked in the rain, for not waterproof), gardens and forages in order to cook seasonally, writes with a quill pen using homemade ink, and walks to the local village when necessary.

Her diary begins in January 2005 and chronicles her monthly chores and activities. She provides recipes, and I have yet to make her oatcakes, but soon nettle soup will be on our table. She kept a careful accounting of the her food categorized by season, purchased or foraged, as well as “What it all Cost.” She works incredibly hard at daily living, keeping warm or cool, gathering firewood, making candles and other chores. At the end of her day, she tries to sit down and read books of the time, but finds that it is difficult to read by the rushlights. Houston confirms my suspicion that working by candlelight was extremely difficult, for I often wonder how much was accomplished by such dim lights.

I have the utmost admiration for Fiona Houston, for mastering the skills needed to survive an eighteenth century year. Her book provides one with both the expertise to follow in her footsteps and the ability to see what one can do in the twenty-first century to live a more considered, ‘greener’ life.

NOTE: It seems only fitting to mark the completion of a second year of ‘on a colonial farm’ after reading of Houston’s eighteenth century life. Thank you, dear readers for joining me.

Fiona J. Houston, The Cottage Diaries My Year in the Eighteenth Century, illustrations by Claire Melinsky, (Saraband, 2009), pgs. 9-10, 44, 71, 214