write me a letter

One of my great pleasures is walking to the mailbox at the end of our driveway and finding inside a personal letter. Handwritten letters are few and far between these days, almost extinct. Otherwise, news, messages and letters arrive instantaneously, delivered electronically, in a consistent typed format. The unique marks of the writer’s hand are gone, no slanting type, no almost indistinguishable smudged words, and no creased paper to unfold and re-fold, rereading as the spirit moves. We don’t think twice about not having access to information, unless we are ‘out of range’ from a cell tower. Remember when the fax machine, the telephone and the telegraph served as the new comers on the block, and their relative speed of transmission then could be termed ‘lightning’?

Let’s go further back in time and situate ourselves in the New England Colonies in the 1630s. Colonists settled along the coast of modern day Long Island (NY), Connecticut and Massachusetts, and eventually further inland, inhabiting Hartford (CT), Windsor (CT) and Springfield (MA). How were letters ‘transmitted’ between these and other settlements? No real roads, nor maps existed, and certainly no postal system. Katherine Grandjean thoroughly examines the ways and means in her book, American Passage: The Communications Frontier in Early New England. She points to the materials needed for a letter: paper, ink quill, and wax. Ink and quills could be made from various found materials. She notes “most colonists brewed their own” ink from a variety of materials: oak galls, charcoal and soot, mixed with various mediums, including water, vinegar, wine and gum arabic. Quills were made from turkey feathers. There were no paper mills in the colonies until 1690, when the first mill opened in Germantown, PA; prior to that, all paper was imported (and thus a scarce and treasured commodity). “Their letters were more irregularly shaped, more congested with script, and more likely to show evidence of ripping and cutting, to make use of excess.” Once written, the missive was folded and sealed with imported European wax for secure passage.

Grandjean tracks the disbursement of the Winthrop family correspondence (John Winthrop arrived in 1630), consisting of 2,856 letters, which have been miraculously saved and archived. She notes that in many instances, the writer and/or recipient would name the courier, a neighbor or a vessel, perhaps. “But the letters also contain glimpses of something else: a marked reliance on Indians. They reflect a hidden geography of Native travelers, weaving across the northeast with English news in hand”. Indeed, the Native Indians knew the paths that laced together the various new communities, making hand carrying more efficient and reliable. Letters contained reports of births and deaths, requests for payment, medical advice, accounts of skirmishes and possible wars. Colonists relied on letters as ‘news’ since no newspapers existed. “But colonial communications were part of the appropriations that accompanied English settlement. Just as their livestock, those famous bovine invaders, overran Native fields and villages, the English themselves–the human wanderers of the northeast–also pulsed through Native Space.”

Imagine being in your cabin preparing a meager meal or working in the woods clearing land for a field or road, and you look up, as a known Indian approaches you with a letter in hand. No regular time or route, and certainly not anticipated. A small conversation would ensue and an exchange of some type as payment. Now, in your hand, held within a very small packet of paper, information, sentiments, observations from another outpost!

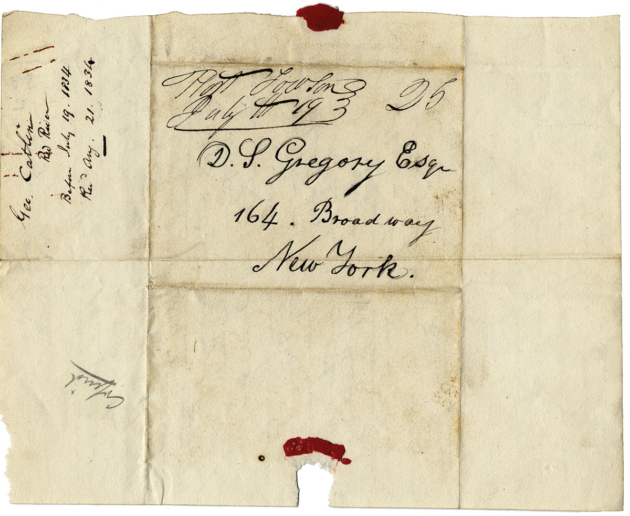

George Catlin letter to D. S. Gregory, July 19-August 21, 1834 Image courtesy of Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution and Princeton Architectural Press

So, dear reader, take the time over the next few weeks to put pen to paper and write a letter or postcard. Enlist a friend or two to start a pen pal group. If you are seeking inspiration, pick up a copy of the book, Pen to Paper: artists’ handwritten letters from the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art edited by Mary Savig. Examine the writing styles, the placement of the text on the pages, the inclusion of a drawn image or collaged element, and take up your pen and paper. Dash off some thoughts and mail them off a friend.

Katherine Grandjean, American Passage: The Communications Frontier in Early New England, (Harvard University Press, 2015), 240, 48, 49, 53, 64, 215.

Pen to Paper: artists’ handwritten letters from the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, edited by Mary Savig, (Princeton Architectural Press, 2016), pas 42-43.

NOTE: Pen to Paper may also be viewed online in this exhibit on Handwritten: a space for pen + paper.

Thanks to the Bidwell House Museum for sponsoring Katherine Grandjean’s enlightening lecture, “Paper Pilgrims: Letter writing and Communications in Early America this summer.

What an interesting blog. Imagine those days! Today, my oldest granddaughter is justifiably proud of herself because she taught herself cursive — note that ‘herself’: her expensive private school never taught her that! Maybe letter writing will come back as all these texters develop arthritic thumbs and thus resort to pen on paper….who knows?