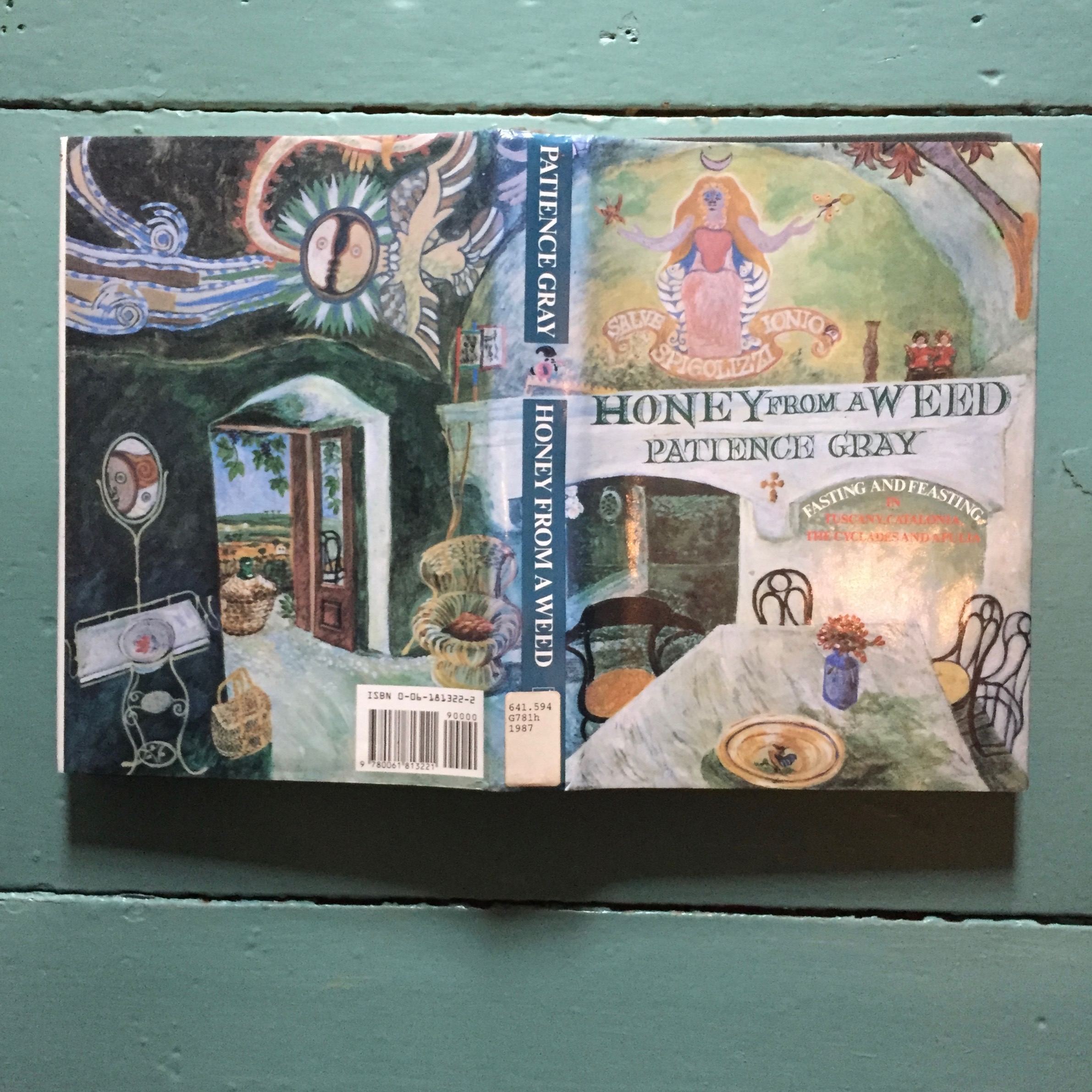

“honey from a weed”

“As Carl Wilkens wrote when we make something with our hands, it changes the way we feel, which changes the way we think, which changes the way we act.” (1)

To make something whole. What does that mean exactly? Does that mean to construct an object from start to finish, as one would carve a bowl from a burl? Or perhaps, to take a discarded or broken item and make it anew, to renew it? To find food, an entire meal, from items deemed ‘weeds’?

As a way to transition into this new year, I set my mind to reading and listening to works by writers and makers. Terry Tempest Williams has been reading me her book on the sacred lands of our National Parks, The Hour of the Land. Many artists have been telling me their ‘making history’ via the Make/Time podcast series. And Adam Federman revealed the life of Patience Gray to me in his new biography, Fasting and Feasting.

Patience Gray, author of the legendary cookbook Honey from a Weed, lived what one could term a spare life, for she and her partner Norman Mommens chose to live “…for more than thirty years in a remote corner of southern Italy–without electricity, modern plumbing, or telephone.” (2) Yet, their lives were rich for the food she gathered and cooked, and for the sculptures he carved from marble, and for the landscape in which they situated themselves.

Gray was quite concerned with the dangers of “consumerland” and wrote about integrating life and art together in her columns for the Observer. In her 1960 article, “Crafts from Obscurity,” she noted, “Can you be touched by the delicate pinks, mauves, magentas, poppy tones in woven hangings without first having seen rock roses, wild mallows, oleander, or cornfields ablaze with poppy, in a landscape of scrub and stone?…Once the outside world has broken in with its promise of Lambrettas and refrigerators and hire-purchase, the self-sufficiency of a village culture is finished.”(3)

What would Gray say to our ‘interconnected world’? Would she relish in the internet and one’s ability to glean information in an instant? It seems rather unlikely, especially as she alludes to these types of modern burdens in an interview on the BBC:

“Life has become burdensome, in a way, in its demands on people. And I can lead them to a bit of daydreaming, which is rather out of fashion now, isn’t it? You could say that I have sort of responded against the present time where I feel that nothing is sacred. It’s a counterpoint to that. Because things are sacred. That’s what I feel.” (4)

Gray wanted her readers to not only daydream but to gather food and sustenance for the mind and soul. “Living in the wild, it has often seemed that we are living on the margins of literacy. This led to reading the landscape and learning from people, that is to first hand experience.” (5)

Each year, I attempt to delve deeper into the landscape directly outside of our front door, not only by observing the seasonal differences, but by also using what is directly at hand for food, healing and dyeing. Over the next months, chapter by chapter, Patience Gray will be my guide to not only the realm of daydreaming, but to the logistics of making whole through our environs.

Terry Tempest Williams, The Hour of the Land: A Personal Topography of America’s National Parks, (New York, Sarah Crichton Books, 2016), pg. 140 (1)

Adam Federman, Fasting and Feasting: The Life of Visionary Food Writer Patience Gray, (White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2017), Introduction(2), pg. 89 (3), pg. 304 (4.).

Patience Gray, Honey from a Weed: Fasting and Feasting in Tuscany, Catalonia, The Cycllades and Apulia, (New York: Harper and Row,1987), pg. 11. (5)

Note: Tune into the Make/Time podcast series.