written words

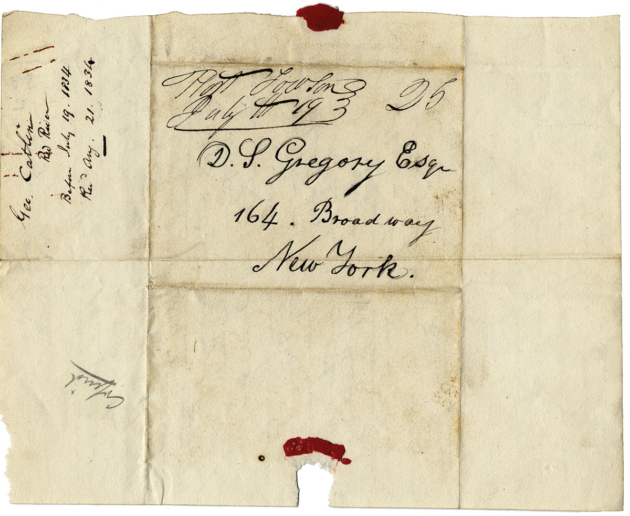

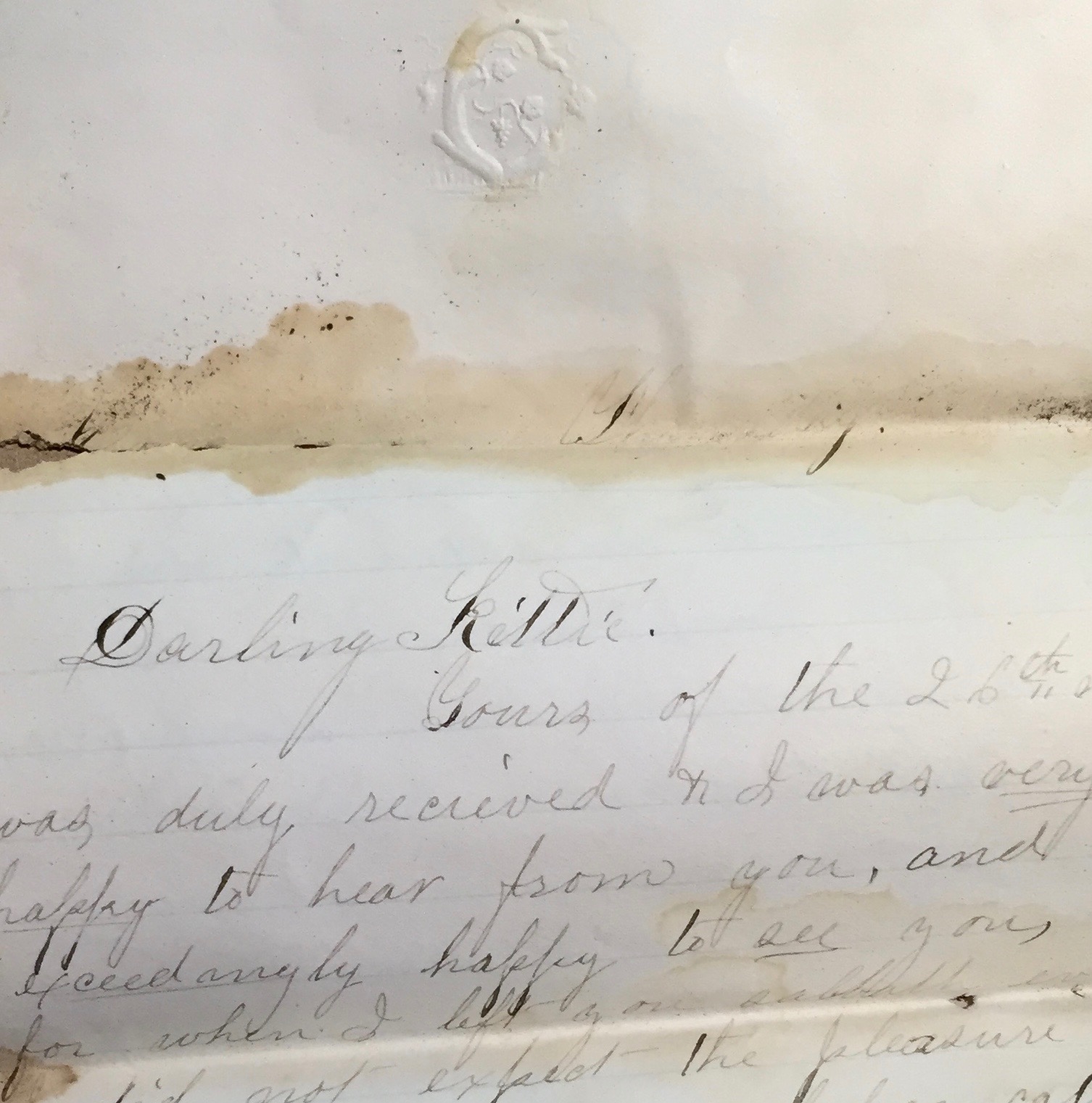

Letters are relics and treasure troves of information, transporting one right back to exact moments in time.

A few years ago, my husband, busy insulating and putting on new clapboards, found a cache of letters in the walls of our old house. These letters were written during 1868-69 from a young man, Joseph, living in our home, to a young woman, Kittie, residing five miles down the road, quite a distance at that time. The bundle only included his letters, which recounted his daily life on this farm, expressed his love for her and told of their eventual break in friendship. Did he ask for the return of the letters or did she bundle them up, delivering them before she headed west? From the inside of the house, there wasn’t a hole in the wall or any other indication what lurked behind. Perhaps, Joseph couldn’t bear to throw them out and sealed them in the wall for safekeeping. Over the past months, I have talked with his relatives, but none knew of his early love for Kittie. Despite my researching at the local historical society, I cannot locate any information about her. Time for more sleuthing.

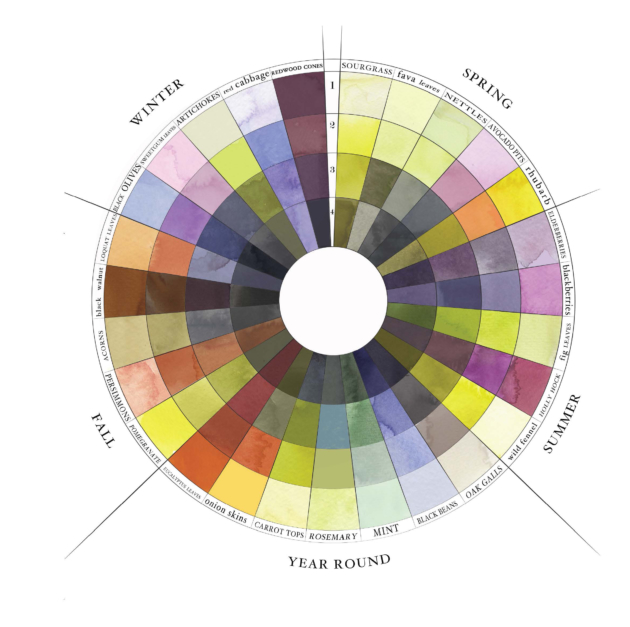

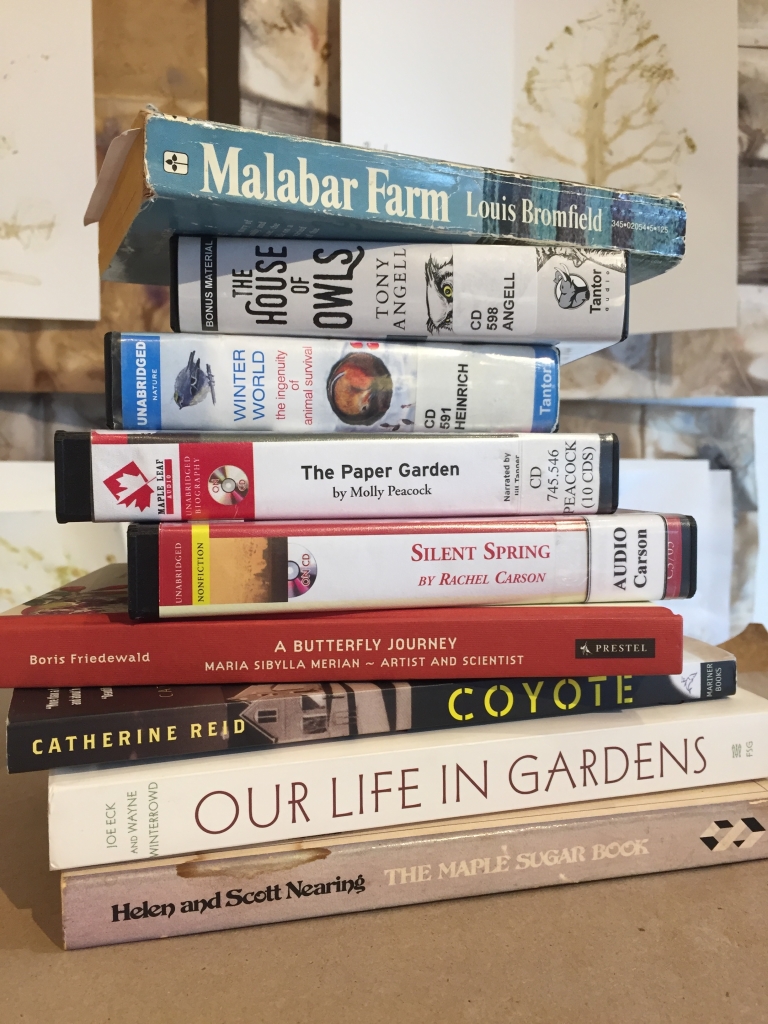

Possibly, reading his correspondence primed me for delving into more volumes of letters. Lately, M.F.K Fisher’s letters (1929-1991) have absorbed me, allowing me to journey along as she struggled with her writing, penned many books, traveled across the country and abroad, and lived a very full life raising two daughters. Even though we only have Fisher’s letters, over time one begins to know her sisters, husbands, family and friends, and follow the path of her life. After listening to the novel The Indigo Girl recounting a distinct chapter of the life of Eliza Lucas Pinckney (1722-1793), I had to read Pinckney’s letters (on which the book is based). Seventeen year old, Eliza was left in charge of her father’s farm in South Carolina. Saddled with debt, she initiated many farming endeavors, including the farming of indigo. Due to its success, many other farms began to grow and harvest indigo. And this morning found me deep into Letters To A Young Farmer, a series of letters written to inspire, bolster and advise new farmers. Each one is penned with passion for the land and the love of farming. All three books are quite different as to time and place and trades, but all offer a glimpse into a how a life was lived and the paths chosen.

“You are so young, so much before all beginning…have patience with everything unresolved in your heart and…try to love the questions themselves as if they were in locked rooms or in a very foreign language. Don’t search for the answers, which could not be given to you now, because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer.”

Rainer Maria Rilke, from Letters to a Young Poet, 1929. (1)

1-Letters to a Young Farmer On Food Farming and Our Future, Princeton Architectural Press, 2017, pg. 1.

Natasha Boyd, The Indigo Girl, Blackstone Publishing, 2017.

M.F.K Fisher, A life in Letters Correspondence 1929-1990 selected and compiled by Norah K Barr, Marsha Moran, Patrick Moran, Counterpoint, 1997.

Eliza Lucas Pinckney, The Letterbook of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, The University of North Carolina Press, 1972.