it’s in the mail

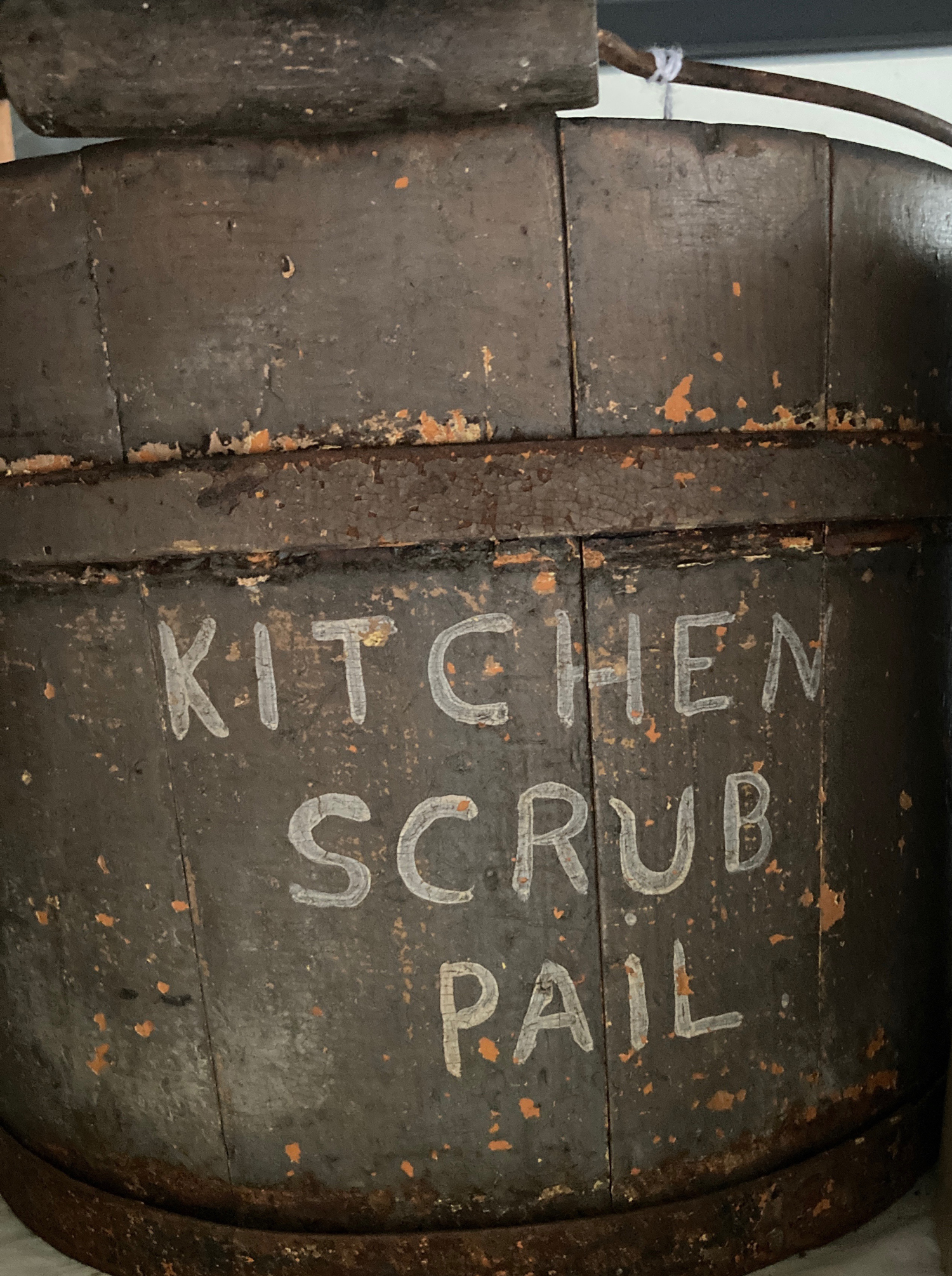

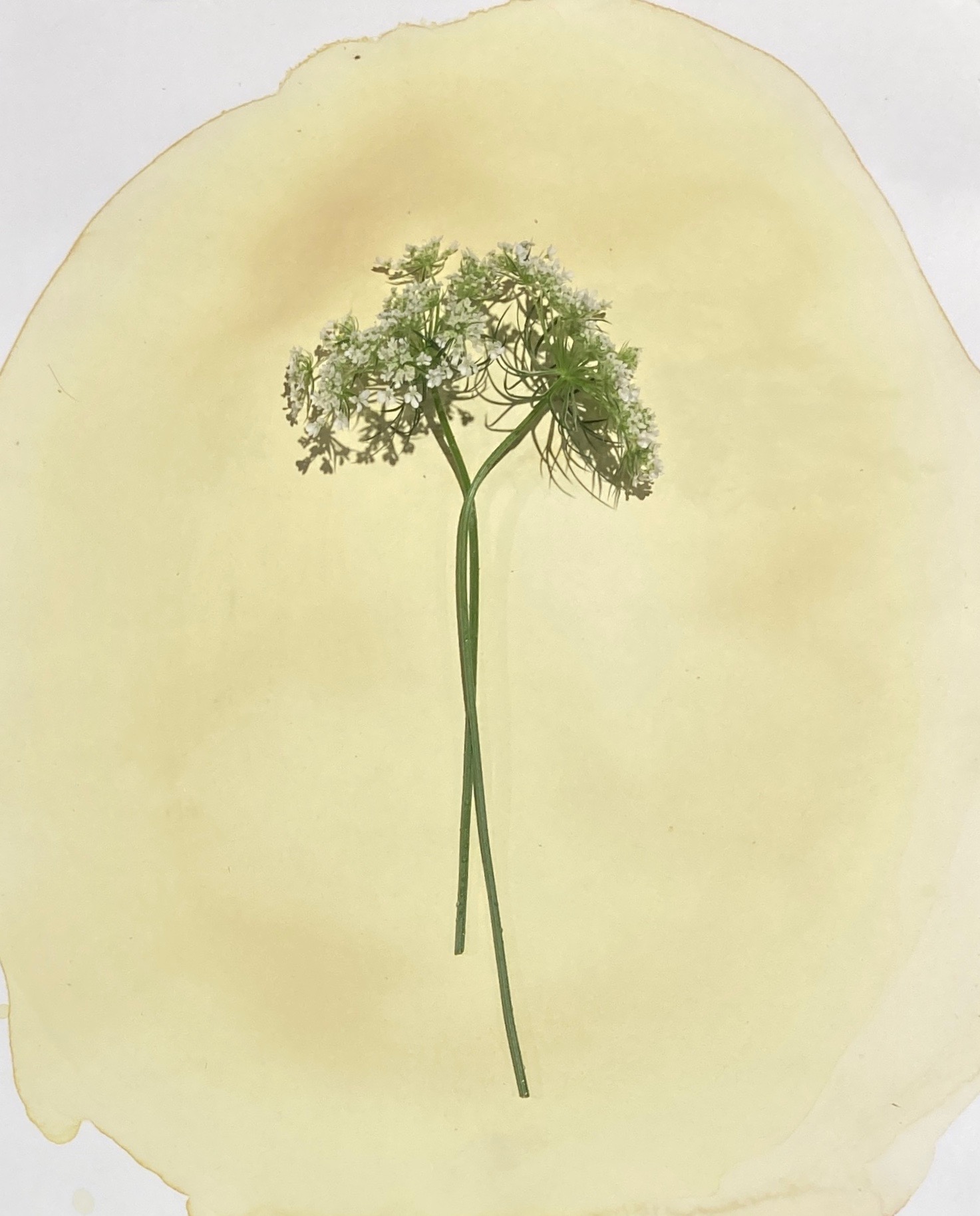

Thursday December 10th marks the poet Emily Dickinson’s 190th birthday. Dickinson sent many poems to her friends in letters and as letters, often with a flower enclosed. During the 1800s, the Shakers communicated amongst their 19 villages with letters, setting aside time in their schedules to read these aloud to the sisters and brethren.

And how do these two strands weave together you might be wondering? These acts of correspondence inspired a project between the bookbinding studio at Camphill Village and me, the artist-in-residence at Hancock Shaker Village.

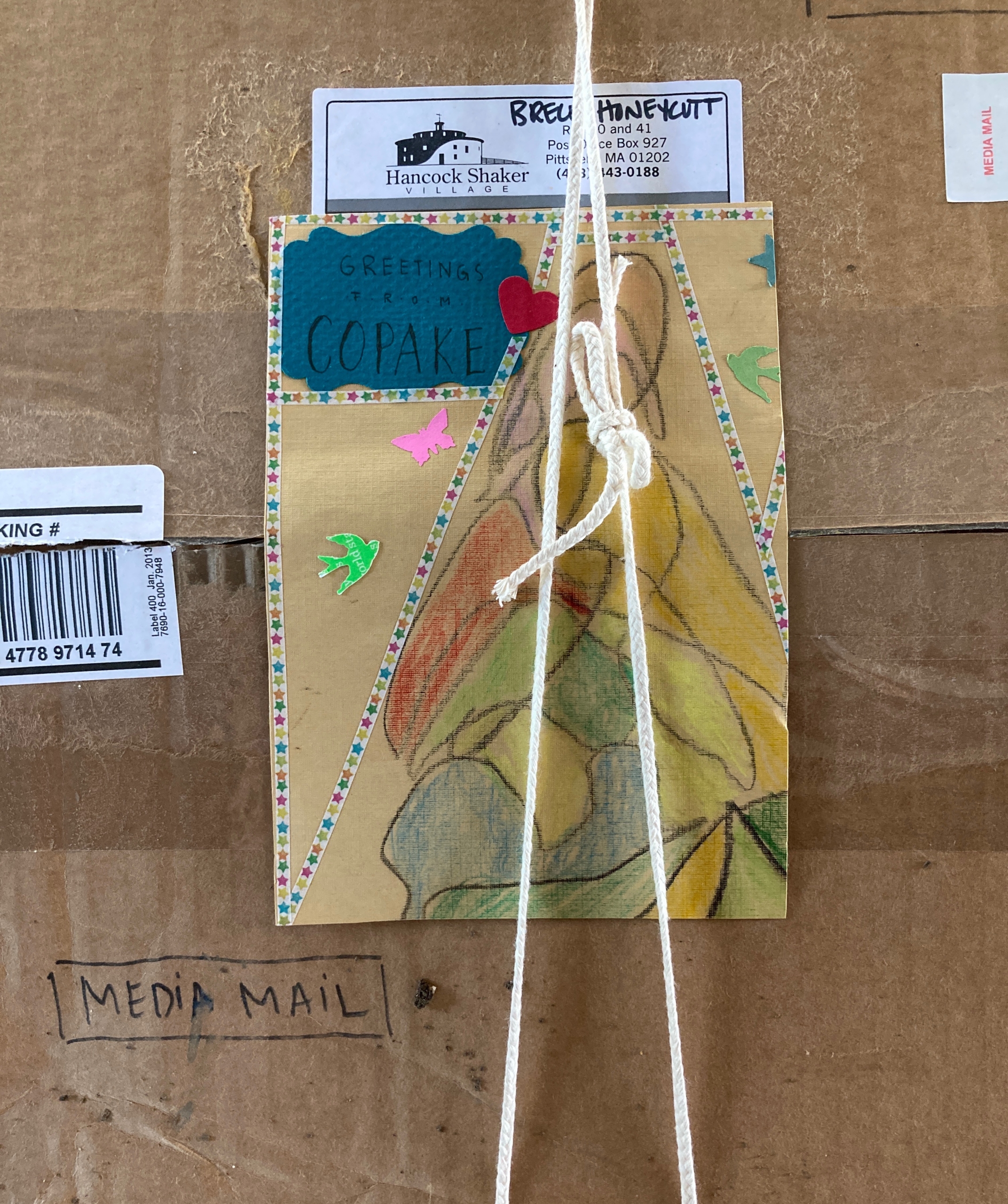

For the past months, we have been sending letters, books, poems and art materials back and forth. This course of action chosen, for we are unable to collaborate in person due to Covid-19.

Recently, I received this from one of my collaborators:

“I just wanted to touch base and thank you for the wonderful creation that we are so fortunate to be inspired by. Every time I see that original envelope my heart leaps with joy. And the poems are such a healthy nourishment for the soul.”

In light of Dickinson’s birthday and in hopes that President-Elect Biden and Vice President-Elect Harris will choose an inaugural poet, we offer a few of the poems that we have shared, “nourishment” for your souls.